INTRODUCTION

Adding a drop to the ocean of tax reforms, the Australian government issued a consultation paper on DPT in May 2016. These are “taxing times”, is the phrase being thrown around these days. The question that may arise in one’s mind would be: what factors called for such changes?

A non-profit group of crusading reporters called the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) shattered the long-held view that offshore bank secrecy was impenetrable. With the press of a button, secrets that have been locked up in vaults for years circumnavigated the globe instantaneously, and authorities’ knowledge about their wealthiest citizen’s finances grew exponentially. These leaks catered as a “significant trigger” behind governments’ reinvigorated scrutiny of “how their countries can collect taxes which are due under national laws.”

They say that technology is a powerful driver of both the evolution and proliferation of innovation. Sadly, for these tech companies, technology itself brought them under the scanner of tax authorities. Such is the irony of life!

It has been reported that since 2013, annual global corporate income tax revenue losses could be between $100-$240 billion (1). As the stakes were high, it was about time to introduce significant amendments in the international taxation playground. Accordingly, on the recommendation of G20, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified 15 actions to curb international tax avoidance. The package of measures is structured around three fundamental pillars: introducing coherence in the domestic rules that affect cross-border activities; reinforcing substance requirements in the existing international standards; and improving transparency, as well as certainty for businesses and governments.

The article discusses the interplay of alternative approach of DPT employed by the UK and Australia to curb tax avoidance with OECD’s recommendations on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). To understand the same it is important to have a background of DPT which is explained below.

WHAT IS DPT?

While DPT has been widely reported as “Google Tax” (2) targeting the digital sector; in fact it applies to a very wide range of transactions across all industry sectors. So what exactly is this Google tax, and how is it supposed to deter tax avoidance?

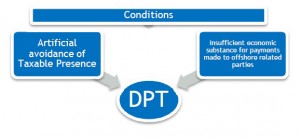

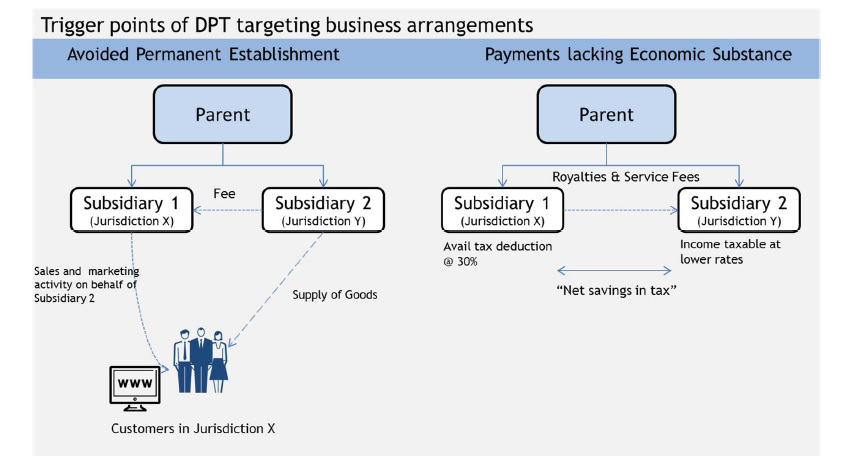

Broadly speaking, DPT is a new tax, proposed and implemented by very few countries. It imposes a penalty on large companies that shift income abroad through certain transactions and corporate structures. The following diagram summarises ‘trigger points’ where DPT can be levied.

It has been hailed as one of the solutions to decode double non taxation and induce companies to pay their fair share of tax, and it targets profits considered to have been diverted from one tax jurisdiction to another. It can apply if there is either a transaction in the global supply chain involving low-tax entities lacking economic substance, or arrangements which have a main purpose of avoiding a tax charge. Please see below for the examples to explain the above ‘trigger points’:

DPT has potentially significant implications for the global supply chains of affected multinational groups, including the very real prospect of “double taxation”.

The DPT was first introduced in the UK and it enabled HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) to re-characterise the supply chain of affected multinational groups and re-compute the profits that, in its view, were just as reasonable to assume would have been earned in the UK and subject to UK corporation tax, had the supply chain not been designed to secure group tax efficiencies.

As the ramifications of the proposed levy were severe; jitters were felt and the world witnessed large global corporations bending down to the rest of time and promising to pay hundreds of millions in taxes to the UK government.

When the UK introduced DPT, it was predicted that other countries would follow suit. Sure enough, the Australian government announced detailed proposals in their recent Federal Budget and has sought public consultation on the implementation of DPT.

AUSTRALIA: FOLLOWING THE UK’S LEAD

As mentioned above, in 2015, the UK introduced a DPT to address international profit shifting arrangements which are designed to avoid having a taxable presence in the UK (the first limb) or which transfer profits earned in the UK to an offshore related party (the second limb).

Following the UK’s lead, with an objective to improve the competitiveness of the Australian tax system to support investment and growth and to clamp down on corporate tax avoidance, Australia earlier introduced the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL) which broadly replicates the first limb of the UK’s DPT and now it proposes to introduce a DPT of its own which will be based on the second limb of the UK’s DPT.

The following section summarises the nuances of the Australian DPT, explaining the applicability and charging mechanism:

- Commencement of DPT: It will apply to income years commencing on or after 1st July 2017 and apply whether or not it’s a relevant transaction (or series of transactions) was entered into before that date (i.e. it’s a retrospective change).

However, in the review process it is clarified that provisional DPT assessment must be issued within 7 years of an entity lodging tax return, therefore it seems that the transaction entered into before that are grandfathered.

- Taxpayers subject to DPT:

- Australian resident entities with annual global income of $1 billion or more; or

- An entity that is a member of a group of entities, consolidated for accounting purposes, which has annual global income of $1 billion or more; or

- Foreign residents having Australian Permanent Establishment (PE)

However, DPT is not intended to target entities that do not pose a significant compliance risk, including significant global entities with small operations in Australia and thereby a ‘de minimus’ threshold has been prescribed which exempts significant global entities with Australian turnover of less than $25 million.

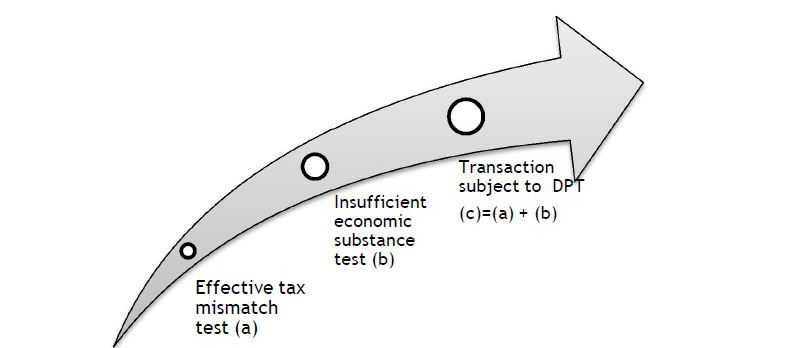

- Transactions subject to DPT: As discussed earlier, DPT addresses a scenario where profits earned are transferred to an offshore related party. However, a DPT charge can be levied only if following cumulative conditions are met:

- The transaction has given rise to an effective tax mismatch

Tax mismatch test is said to be fulfilled when the ‘effective tax savings’ for a company is more than 20%. This is explained by way of the following example:

Company A made a tax deductible payment to its related party i.e. Company B and availed tax benefit of $100;

Company B, resident of a state which has lower tax rate; paid $603 as tax on above income;

As the tax liability for Company B in its home jurisdiction is less than $80, i.e. ‘effective tax savings’ is more than 20%, an effective tax mismatch will arise.

- The transaction has insufficient economic substance

Determination of this test will be based upon the perusal of the information available at the time to the review (tax assessments), it may be reasonable to conclude that the transaction was designed to secure the tax reduction.

It may be argued that the above test is subjective and will lead to a number of litigations. In an attempt to allude the same, Australia has followed an approach that is similar to the one followed by the UK, whereby if the non-tax financial benefits of the arrangement exceed the financial benefit of the tax reduction, the arrangement will be taken to have sufficient economic substance.

Hence if both of the above conditions are fulfilled, the Australian Tax Office (ATO) may undertake a DPT assessment. However, it is pertinent to note that the Commissioner will have a broad discretion to not to apply DPT where the Commissioner considers the transaction or arrangement to be low risk.

INTERPLAY OF DPT – A CONCEPT WITH OECD’S BEPS ACTION PLANS AND TAX TREATIES:

As a policy choice, the DPT arguably reduces the pressure on the OECD BEPS initiative for a wholesale change to global PE and transfer pricing rules.

The DPT’s impact on international tax treaties can be seen from two perspectives. On one hand, the DPT is disruptive of tax treaty conventions because it is fundamentally against the physical presence standard of PE status outlined in the OECD Model Tax Convention. If countries continue to adopt DPT-like policies, then the traditional concept of PE status will be eroded and may even become obsolete.

On the other hand, it may be argued counterintuitively that the DPT may instead protect the concept of PE status. By specifically targeting income shifting by multinational corporations, the DPT eliminates the necessity to modify and dilute the current concept of PE status to address income shifting.

While both arguments have some truth, the former is stronger because even if the DPT does not directly alter PE status roles (and in this sense preserves them), the DPT attacks the fundamental principles of PE status and in doing so, effectively weakens PE status as an international standard.

Moreover, the DPT encourages countries to take unilateral actions that are antithetical to progress in international tax policy. The DPT emerges as the OECD released its final reports for the internationally-coordinated BEPS project, with BEPS Action Plan 7 tightening exclusions to PE status and expanding the definition of PE status to include commissionaire agreements. By encouraging unilateral action, the DPT may help countries collect additional tax revenues in the short term, but it ultimately hinders international cooperation and will likely result in incongruous tax policy across jurisdictions.

PARTING THOUGHTS:

It is frustrating for countries like Australia and the UK to deal with corporate tax avoidance among multiple other revenue issues, it seems that the DPT may erode international tax treaty conventions and disrupt international coordination on tax issues. It is ultimately important for policymakers to keep in mind that tax policy should not be legislated in a vacuum, just as a country does not exist in one.

The response of other countries will be of great interest. On one hand the legality of DPT will no doubt be questioned. Equally other countries may see DPT as a model to tackle perceived avoidance in their own jurisdictions.

It seems that both countries are firing warning shots across the bows of US MNCs, making it clear that irrespective of BEPS measures which may take years to come into effect, unilateral attacks will be launched. The US may begin to threaten retaliation, and it may be that the threat of other countries taxing their multinationals will finally lead the US to implement reforms in its own tax system. After all, if US companies are going to pay more tax, surely the IRS will want to take the first bite of the cherry.

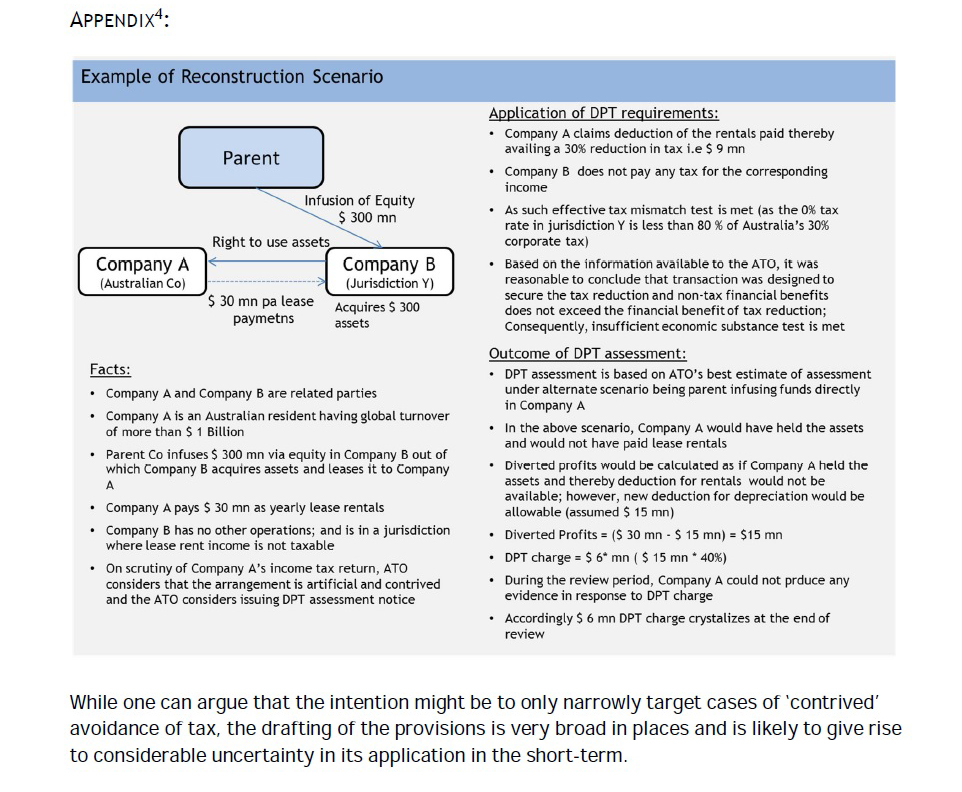

Also, as we describe the UK and Australian DPT in these broad terms, the fundamental difficulty of these policies becomes uncomfortably apparent. How is the government supposed to identify when profits “should have” been reported domestically, rather than abroad? Or what was the best possible way in which one could have entered into the transaction? (Illustration attached as appendix).

Only time will unfold the answers to the above questions.

Furthermore, with deferral application of the Indian General Anti-Avoidance Rules (‘GAAR’) it would be interesting to witness India’s position on this “billion dollar question” of offshore transfer of profits. Will it take a conservative view and make fundamental changes to the concept of PE and amend treaties with various countries and wait for an indefinite period or will it take a course of action similar to the UK and Australia?

In a nutshell, these are “taxing times” indeed!