Is Safe Harbour an Option for Emerging Economies?

One of the novelties resulting from the OECD/G20 action plan vs. base erosion and profit shifting (the BEPS plan) is the suggestion of a safe harbour in relation to low value-added intercompany services. Said safe harbour, under certain limitations, would enable the transfer of certain types of support services (not associated in any way to the main business activity of the recipient) at total cost plus a profit margin of 5%. The use of safe harbour by multinational groups could bring tax consequences in emerging economies, since the transfer of costs and expenses associated to a service, plus the aforementioned utility margin, does not necessarily match arm's length expenses of the recipient, and may, potentially, lead to conflict with tax authorities.

Background

On October 5 of 2015, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published the final reports of the BEPS plan. Action 10 (other high risk transactions) brought some changes to the transfer pricing treatment granted to intragroup services, specifically “low value-added services”. The OECD understands low value-added services as those that: i) are of a supportive nature, ii) are not part of the core business of the MNE group, iii) do not require the use of unique and valuable intangibles and do not lead to the creation of unique and valuable intangibles, and iv) do not involve the assumption or control of substantial or significant risk by the service provider and do not give rise to the creation of significant risk for the service provider. By using certain rules, which involve a clear identification of the costs to be transferred and the use of common allocation methods to all beneficiaries, the transfer of total costs associated to said services, plus a profit margin of 5%, is possible (so long as there are no internal comparables). The use of this simplified approach also grants the removal of the benefit test historically required in order to demonstrate the arm´s length condition of intercompany services and consequently simplifies an always difficult process benefiting the taxpayers.

The adoption of the new rule is suggested in two stages. The first of them involves implementation by the highest possible number of countries before 2018. The second stage involves developing the rule regarding the maximum charge limit for intragroup services, and catering for different issues necessary for implementation, in order to achieve the highest possible adherence to this proposal.

With this background, does this provision have chances for success in emerging economies?

Alternative cost for the services recipients

One of the most frequent sources of conflict between tax authorities and taxpayers stems from intragroup services. The incidence of this type of transactions in emerging economies is high, and frequently the charge is completely disassociated from the functional structure of the recipient. Coupled with this, the fact that the amount charged may appear to be significantly higher than the alternative cost of the service in the domestic market, encourages tax authorities to reject the deduction of expenses resulting from intercompany charges.

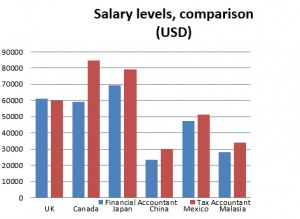

Based on the above, is the mark-up suggested by the safe harbour a problem? Obviously not, the issue lies with the cost associated to the services, not with the mark-up itself. To illustrate this situation (at risk of oversimplification), the following are cost examples in USD of the same position in different markets (with information supplied by Hays, figures in USD):

| Position | UK | Canada | Japan | China | Mexico | Malaysia |

| Financial Accountant | 61191.5 | 59028.5 | 69374.5 | 23207 | 47500 | 28231 |

| Tax Accountant | 59905.5 | 84614.5 | 79305.5 | 29933.5 | 51109.5 | 34179 |

As it can be appreciated, the cost for the same position in developed countries and emerging economies is significantly different, and in a worst case scenario (for instance: tax manager, Japan vs. China) it can be more than 60% higher (obviously, a case-by-case review of each operation is necessary). But, as it is, and considering that these type of services are in principle replaceable in the recipient country, absorbing the function at the source cost would not be justified unless said cost is shared with other subsidiaries, and the resulting cost is lower than or equal to the domestic market value. This conclusion should trigger a profound analysis of the functions and of the amounts to be distributed and of the allocation keys to be used within multinational group, considering the alternative cost for recipient subsidiaries.

It is also important to consider that there are additional limitations to achieve maximum adherence to the rule in emerging economies, maybe the most challenging issue is the enactment of national rules, which is frequently a lengthy process, and which may result in differences regarding the application of a global transfer pricing policy for multinational groups.

Conclusions

Undoubtedly, issuing transfer pricing rules in matters of low value-added services serves the purpose of decreasing the administrative burden generated by these types of transactions for multinational groups. However, the success of this rule remains uncertain as there is still a lack of consensus to this day, and an early application of this provision by multinational companies based in developed countries could trigger double taxation scenarios in relation to their subsidiaries in emerging economies. Therefore, and in order to avoid an uncertain tax scenario, it is suggested that multinational groups thoroughly assess the adoption of said rule, and ensure the potential consequences of its use.