Managing risks of long term energy pricing agreements

Dr Paul Edge of EDP will be speaking at QuantMinds International in Lisbon this May, as part of the FX, Commodities & Trading Innovations stream. Here he looks at how to measure and manage the risks created by signing contracts that guarantee fixed energy prices over the long term.

Long term commercial contracts (LTCCs), long term supply contracts (LTSC) and power purchase agreements (PPAs) allow energy suppliers to sell to purchasers a certain amount of energy (gas, oil, electricity) for a fixed price at various points in the future. This stabilizes future cashflows for both parties, reducing risk and allowing companies to raise more debt financing at cheaper rates.

These contracts have value the moment an agreement on price and volume has been made. This value is stochastic and based on the future expectations of the underlying energy price. If, say in a year’s time, expectations of future market prices are lower than originally expected then the contract will have positive value for the supplier. If future expectations are higher, then the contract is more valuable to the purchaser.

Now there are two questions.

- How will the value of this contract change over time?

- What protection is available in the case that the counterparty defaults and a new deal must be brokered on considerably worse terms?

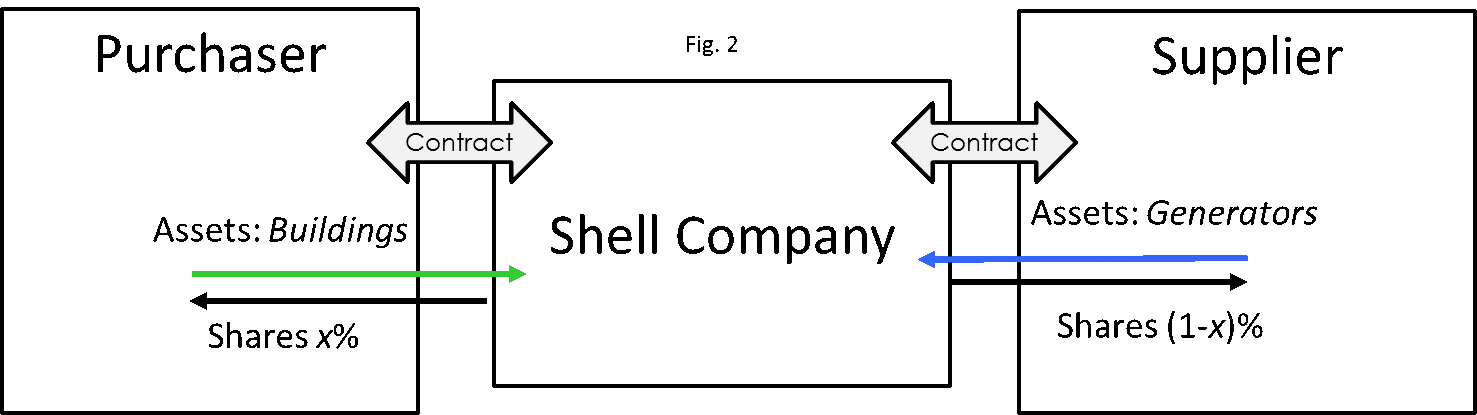

Tackling the first question requires a model of future energy prices. A model not just of what the current expectations of prices are, but also of all the possible future price expectations. An accurate risk assessment requires the model to provide information about both the maximum value of the contract (the risk) and the expected value if the other party were to default (the credit cost). Fortunately, this is a solved problem and I will be presenting a simplified long-term pricing model (see Fig. 1, freely downloadable from SSRN) at the upcoming QuantMinds International.

The second question is of a more practical significance. Taking no mitigation measures would leave the counterparty ranking alongside other unsecured creditors. For large volume contracts, this creates a significant credit risk.

One possibility could be to require margining by both counterparties on a timely basis, however, even just a small parallel increase in the price curve can have large effect on the contract value. For instance, a price increase of €1 would not only increase the value of the next cashflow by €1 but also all future cashflows. The longer the contract, the greater the sensitivity to price changes. Mitigating the credit risk in such a way requires large amounts of cash to be tied up in collateral, for every individual signed contract. Alternatively, credit default insurance may be purchased, often for a costly premium.

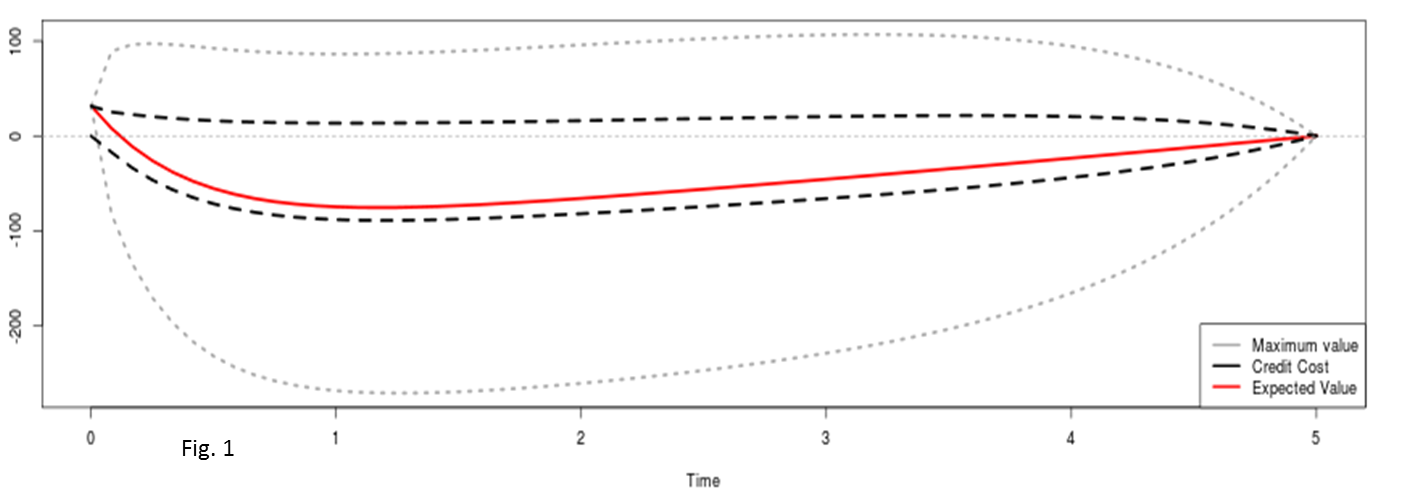

A new, innovative approach would be to create a shell company to mitigate the risks of the contract. Into this shell company, both the Supplier and Purchaser place assets of a value equal to the maximum loss that the PPA can inflict on the counterparty. Then, the proportion of shares in this new shell company are divided to match the value of the assets placed in the company. Matching offsetting contracts are then signed between the shell company and both the Purchaser and Supplier to mirror a more traditional setup (see below).

As the value of the underling agreement changes over time, so does the share allocation to each counterparty. This allows value held by each counterparty to dynamically match the exposure of the underlying contract and, upon default, the remaining creditor has an immediate claim over the fair proportion of the shell company’s assets. Unused illiquid, indivisible capital assets have been turned into a useful, liquid collateral which meet the underlying economic needs.

Of course, there are many downsides to such a structure.

- One side may not have enough suitable assets to place in the shell company

- There may be legal objections that could be raised in the issuing jurisdiction

- Such an unfamiliar structure would require a large amount of explanation to meet regulatory and rating agency approval.

- The accounting impact can create multiple problems (especially on a consolidated basis)

- Grandfathering into existing agreements will be difficult, so this solution is probably only for new business

Finally, there needs to be a trusted third party that can impartially carry out the required calculations accurately and on demand. This would be a perfect use case for a blockchain smart contract, although discussing that subject would easily fill another of these articles…