| By Nicole Robins, Mohammed Khalil and Vidur Taneja[1] |

Since 2014, the tax arrangements of multinationals with EU-based subsidiaries have been under the European Commission’s State aid spotlight. This culminated in August 2016 with the European Commission’s announcement that Apple’s tax arrangements in Ireland constituted illegal State aid, with Ireland required to recover €13bn from Apple’s Irish subsidiaries. This landmark case constitutes the Commission’s largest-ever State aid recovery order from a single company. This follows the Commission’s negative State aid decisions in relation to the tax arrangements of Starbucks, Fiat Finance and Trade, and 35 Belgium-based multinationals. This article discusses the Commission’s focus in these investigations on whether tax arrangements confer a selective economic advantage, and the important role for economic and financial analysis to mitigate State aid risk in corporate tax arrangements.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the Commission has focused its attention on whether tax rulings approved by Member States constitute illegal State aid.

This started in June 2013 with the announcement that tax rulings agreed by seven Member States were under investigation, with the inquiry extended to all Member States in December 2014.[2] In October 2015, the Commission concluded that illegal State aid had been granted to Fiat Finance and Trade and Starbucks by Luxembourg and the Netherlands respectively.[3]

In the backdrop of this heightened State aid scrutiny on the tax arrangements of multinationals, in August 2016, the Commission handed down its largest-ever negative State aid decision for an individual measure, requiring Ireland to recover €13bn plus accrued interest from Apple.[4] This followed an in-depth investigation launched in July 2014, covering alleged tax advantages granted to Apple in the form of two tax rulings in 1991 and 2007.[5]

Box 1.1 Overview of the State aid investigation of Apple

The Commission concluded that two tax rulings granted by Ireland in 1991 and 2007 to Apple’s Irish subsidiaries—Apple Sales International, ASI, and Apple Operations Europe, AOE—constituted illegal State aid in favour of Apple.According to the Commission, the tax rulings endorsed an artificial allocation of profits that had no economic justification, with the majority of ASI’s and AOE’s profits allocated to ‘head offices’ that existed only on paper, and were not subject to tax in any country. As a result, the Commission concluded that the majority of ASI’s and AOE’s profits remained untaxed. For example, according to the Commission, the effective corporate tax rate paid by ASI was as low as 0.005% in 2014.The Commission has directed Ireland to recover €13bn plus interest from Apple. However, a novel aspect of the decision is that the aid to be repaid to Ireland can be reduced if other countries require ASI or AOE to pay more tax, and/or if ASI and AOE are required by the US authorities to make additional payments to their US parent to fund research and development.

Source: European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion’, press release, 30 August, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2923_en.htm, accessed on 7 November 2016.

As at the time of writing this article in November 2016, the high-profile investigations continue into the tax rulings approved by Luxembourg for Amazon and McDonald’s, with a further 1,000 tax rulings under review.[6]

This article discusses the Commission’s framework for determining whether tax rulings constitute State aid, with illustrations based on the investigation of Apple’s tax arrangements in Ireland. The article concludes by highlighting the important role of economic and financial analysis in mitigating State aid tax risk.

2 Overview of the Commission’s State aid framework

2.1 The general State aid framework

Under the Commission’s framework for State aid control, measures provided by public authorities constitute State aid if they meet all of the following four criteria summarised below.

Box 2.1 The general criteria for a measure to be State aid

- State resources: the measure involves an intervention by the state or through state resources. The measures can take a variety of forms, such as grants, loans, guarantees on loans and tax exemptions, for example.

- Selective to certain undertakings: the measure is selective in nature (i.e. the treatment of a company by a Member State differs from the treatment of other companies that are in a ‘comparable legal and factual situation’).

- Provision of an economic advantage: the measure provides an economic advantage to the recipient that could not have been obtained under normal market conditions.

- Potential to distort competition and trade: the measure distorts or has the potential to distort competition and trade across the EU.

Source: European Commission, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/overview/index_en.html, accessed on 26 October 2016.

In the Apple Opening Decision, the Commission argued that as tax rulings are issued by Irish Revenue, part of the Irish State, the rulings were imputable to the state. Furthermore, according to the Commission, as the tax arrangements resulted in lower taxes collected from Apple’s Irish subsidiary, this represented a loss of state resources.Under the Commission’s framework, it is relatively straightforward to demonstrate that tax rulings involve state resources and have the potential to distort competition and trade.[7]

- As Apple is a multinational with operations in the EU, under the Commission’s framework, any aid to Apple’s subsidiaries has the potential to distort competition and trade between Member States.

Therefore, the most contentious questions in these cases relating to whether tax rulings are selective and confer an economic advantage to the beneficiary.

2.2 Joint assessment of selectivity and economic advantage

Although the concepts of selectivity and economic advantage are closely related, they are usually assessed separately in State aid cases.[8] However, in the tax State aid cases, the Commission often evaluates these two criteria together by presuming that, for individual measures, an economic advantage is sufficient to demonstrate selectivity.[9]

In particular, the Commission’s assessment in fiscal State aid cases involves examining whether the tax arrangements deviate from the reference system. Under the Commission’s approach, the reference system is defined broadly as the national corporate tax system in the Member State that aims to tax all companies, irrespective of their structure. In other words, the Commission’s approach to defining the reference system presumes that multinationals and independent companies are in a comparable legal and factual situation.[10]

The Commission’s presumption that an economic advantage is sufficient to establish selectivity effectively reduces the steps of the analysis to an assessment of whether the tax arrangements confer an economic advantage.

2.3 Do tax arrangements confer an economic advantage?

In its Opening Decision for Apple, the Commission’s assessment of whether the tax rulings granted an economic advantage to ASI and AOE was based on the hypothetical market operator test. Under this test, the Commission examined whether by accepting the tax rulings, the Irish State acted in a way that is line with a hypothetical market operator which maximised profits.

the tax authorities should compare the method to the prudent behaviour of a hypothetical market operator, which would require a market conform[ing] remuneration of a subsidiary or a brand, which reflect normal conditions of competition[11]

In order to estimate the level of profits that would have been taxed by a hypothetical market operator, it is examined whether the terms and conditions of transfer pricing arrangements (i.e. prices of goods and services sold between companies of the same multinational group) are in line with those between independent companies in comparable transactions. This is referred to as the ‘arm’s-length principle’. As noted in the Commission’s Opening Decision for Apple:

The Court of Justice has confirmed that if the method of taxation for intra-group transfers does not comply with the arm’s length principle, and leads to a taxable base inferior to the one which would result from a correct implementation of that principle, it provides a selective advantage to the company concerned.[12]

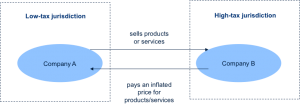

As transfer pricing impacts the profit allocation between different subsidiaries of the same corporate group, the objective of arm’s-length pricing is to avoid multinationals shifting profits from high-tax jurisdictions to low-tax jurisdictions, as illustrated below.

Figure 2.1 Illustrative example of a transfer pricing mechanism

While the hypothetical market operator terminology has been dropped by the Commission in its Final Decisions for Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade—it is also expected to be dropped it in its Final Decision for Apple—the arm’s-length principle remains at the core of the Commission’s assessment of economic advantage in fiscal cases.

The OECD has provided guidelines on the application of arm’s-length pricing, as summarised in Box 2.2 below.

Box 2.2 OECD guidelines on arm’s-length pricing

Traditional transaction methods: comprise methods that approximate an arm’s- length price for specific intra-group transactions, such as the price of certain goods or services. These methods include:

- Comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method—comparison of the prices charged in intra-group transactions with those charged in similar transactions between independent companies;

- Cost plus method—comparison based on costs incurred by suppliers in inter-group transactions, plus a profit mark-up;

- Resale price method—comparison based on prices at which products/services purchased from an associated enterprise are resold to an independent enterprise, with adjustments for selling costs.

Transactional profit methods: these methods compare the profitability of the subsidiary in question with the profitability of comparable independent companies.

- Transactional net margin method—comparison of the profitability of the subsidiary in question against the profitability of other subsidiaries of the same multinational, and/or the profitability of similar independent companies;

- Transactional profit split method—assessment of the allocation of profits between different subsidiaries of the multinational based on the division of profits expected by independent companies. This method was followed in the transfer pricing report in the Apple case.

Source: OECD (2010), ‘Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations’, 16 August.

Therefore, it is important that tax rulings are underpinning by robust economic and financial analysis before the start of these rulings, as explained in the subsequent section.In the tax State aid cases, the Commission has expressed a strong preference for one of the traditional transaction methods—the CUP method—on the basis that this method provides the most reliable approximation of the arm’s-length principle.[13] Furthermore, the Commission has stated that tax arrangements could still confer an economic advantage even if they are based on one of the other OECD methods, particularly if an alternative method would have led to a different outcome.[14]

3 How can economic and financial analysis be used to reduce State aid tax risk?

The OECD arm’s-length pricing methods rely heavily on identifying comparable transactions between independent companies. Furthermore, in order to ensure the accuracy of the comparison, adjustments may also be required to control for differences in these transactions. For example, in its Opening Decision for Apple, the Commission noted that:

The application of the arm’s length principle is generally based on a comparison of the conditions in an intra-group transaction with the conditions in transactions between independent companies. For such comparisons to be useful, the economically relevant characteristics of the situations being compared must be sufficiently comparable.[15]

This is also consistent with the Commission’s Decisions in other cases.

Tax rulings cannot use methodologies, no matter how complex, to establish transfer prices with no economic justification[16]

In light of the Commission’s increased scrutiny on the tax arrangements of multinationals, it is, therefore, critical to present evidence in the transfer pricing report, prior to the start of the tax ruling, that the ruling is underpinned by robust economic and financial analysis.

For example, in the Apple Opening Decision, the Commission argued that as the methods used to determine profit allocation to ASI and AOE result from a negotiation rather than a pricing methodology, this suggests that the agreed method is not on an arm’s-length basis.[17] Moreover, the Commission argued that the choice of operating costs as a profit indicator was not justified while applying the transactional profit method in the transfer report.

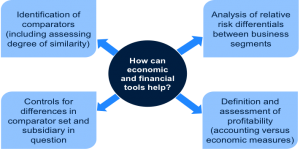

As summarised in Figure 3.1, there are a number of different ways in which economic and financial tools can be used to ensure the robustness of the application of the arm’s-length principle.

Figure 3.1 How can economic and financial tools help in evaluating the arm’s-length principle?

Source: Oxera.

4 Conclusions

In August 2016, the Commission concluded that the 1991 and 2007 tax rulings issued by Ireland led to an artificial profit allocation of profits for the Irish branches of ASI and AOE away from Ireland to a ‘head office’ where they remained untaxed. This was found to be in violation of the arm’s-length principle, and therefore constituted illegal State aid in favour of Apple.

This landmark Decision is of paramount importance to the investigations of tax rulings, given the size of the recovery amount and because it highlights the risk that a State aid investigation could start several years after a tax arrangement is agreed (the first tax ruling was agreed in 1991).

Commentators, including the US Treasury, have expressed concerns on the Commission’s application of the arm’s-length pricing principles in such cases, and these are likely to be a key point of the appeals of recent decisions, the outcome of which will not be known for some time.[18] It is also possible that the investigations could lead other tax authorities to retroactively seek recoveries from US and EU companies.[19]

Given the increasing weight placed by the Commission on economic evidence, in particular, with respect to the assessment of the application of the arm’s-length principle, it is more critical than ever to ensure that tax arrangements are underpinned by robust economic and financial analysis in order to mitigate State aid risk.

[1] Nicole Robins heads Oxera’s State aid team. Mohammed Khalil is a Consultant at Oxera and specialises in State aid. Vidur Taneja is an analyst at Oxera and specialises in the financial aspects of State aid cases. Oxera is an independent economics and finance consultancy with a large State aid practice that has worked on an extensive number of State aid cases, based in Brussels, Berlin, Oxford and London.

[2] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid: Commission extends information enquiry on tax rulings practice to all EU Member States’, 17 December.

[3] European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on State Aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October; and European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on State Aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October. These Decisions are currently under appeal.

[4] European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion’, press release, 30 August, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2923_en.htm, accessed on 7 November 2016. Both Apple and Ireland have announced their intentions to appeal this decision.

[5] At the time of writing this article in November 2016, the Commission’s Final Decision for Apple is not yet publicly available. Therefore, the insights in this article from the Apple case are mainly based on the Commission’s Opening Decision.

[6] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38944 (2014/C) — Luxembourg: Alleged aid to Amazon by way of a tax ruling’, 7 October; and European Commission (2015), ‘State aid SA.38945 (2015/C) (ex 2015/NN) — Luxembourg: Alleged aid to McDonald’s’, 3 December.

[7] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) — Ireland: Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June, paras. 48–51.[8] As an example, see European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 1 October 2014 on the State aid SA.21121 (C29/08) (ex NN 54/07) implemented by Germany concerning the financing of Frankfurt Hahn airport and the financial relations between the airport and Ryanair’, Official Journal of the European Union, 24 May.

[9] European Commission, ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on State aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October; Case C-15/14 P Commission v MOL ECLI:EU:C:2015:362, para. 60; and Case T-385/12 Orange v Commission ECLI:EU:T:2015:117.

[10] The appropriateness of this approach is the topic of the appeals by the Netherlands and Luxembourg of the Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade decisions. For further details, see General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 23 December 2015 — Netherlands v Commission, Case T-760/15 and General Court (2015), ‘Action brought on 30 December 2015 — Luxembourg v Commission’, Case T-755/15.

[11] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) — Ireland: Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June, para. 56.

[12] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) — Ireland: Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June, para. 55.

[13] European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on State Aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October, para. 245.

[14] European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on State Aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October, para. 264.

[15] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) — Ireland: Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June, para. 14.

[16] European Commission (2015), ‘Commission decides selective tax advantages for Fiat in Luxembourg and Starbucks in the Netherlands are illegal under EU State aid rules’, press release, 21 October.

[17] European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) — Ireland: Alleged aid to Apple’, 11 June, para. 58.

[18] See US Department on the Treasury White Paper (2016), ‘The European Commission’s Recent State Aid Investigations of Transfer Pricing Rulings’, 24 August.

[19] Jopson, B. and Beesley, A. (2016), ‘US in last-ditch effort to quash Brussels tax demand on Apple, Sharp escalation of transatlantic feud over bill for billions of euros’, Financial Times, 24 August.