Valuation multiples move up and down. Yet for the past 30 years, the average multiple of EBITDA paid for public assets has almost always topped that paid for private assets. In fact, there have been only three periods historically when private multiples generally exceeded the public average: during the “Barbarians pat the Gate” era of the mid-1980s, during the exuberant run-up to the recent global financial crisis, and now.

But is this becoming a new normal?

The Barbarians era and the pre-crisis boom were short lived, partly because heavy activity in public-to-private deals eventually helped buttress public multiples. P2P activity is strong this time around, too, but as we note in Bain’s 10th-anniversary Global Private Equity Report, a number of factors make it worth asking if something has changed fundamentally in the way investors view the public and private markets. If so, it will have clear implications for PE firms navigating a hotly competitive environment.

Public assets typically command higher valuations because investors are willing to pay a premium for more liquidity and transparency. The universe of investors is also broader, enabling the public markets to attract massive flows of capital. Nothing has really changed in that regard. But a lot has changed on the private side of the ledger. Investors have never been more drawn to the private markets than they are today, and it’s plausible this is leading to long-term change in valuations.

The flow of capital into the private markets is unprecedented. Financial engineering, high-speed computing and the loosening of financial regulations have unleashed a superabundance of financial assets over the past 25 years, transforming the equity and debt markets. Global financial capital increased 53% from 2000 to 2010, reaching some $600 trillion, or 10 times real global GDP. Bain’s Macro Trends Group projects that it will reach approximately $900 trillion by the end of 2020. At the same time, institutional investors are steadily increasing their allocations to private equity.

An unprecedented amount of capital chasing a limited number of assets has driven buyout multiples to record highs. It has also given companies financing choices they’ve never had before. Companies can now tap private equity or institutional capital with relative ease and borrow at historically low rates, bypassing the myriad costs and hassles of going public. The number of US public companies has declined approximately 45% since its peak 20 years ago. The number of IPOs has also plummeted. During the 1990s, the US market averaged 652 offerings a year. Last year, the total was around one-third of that.

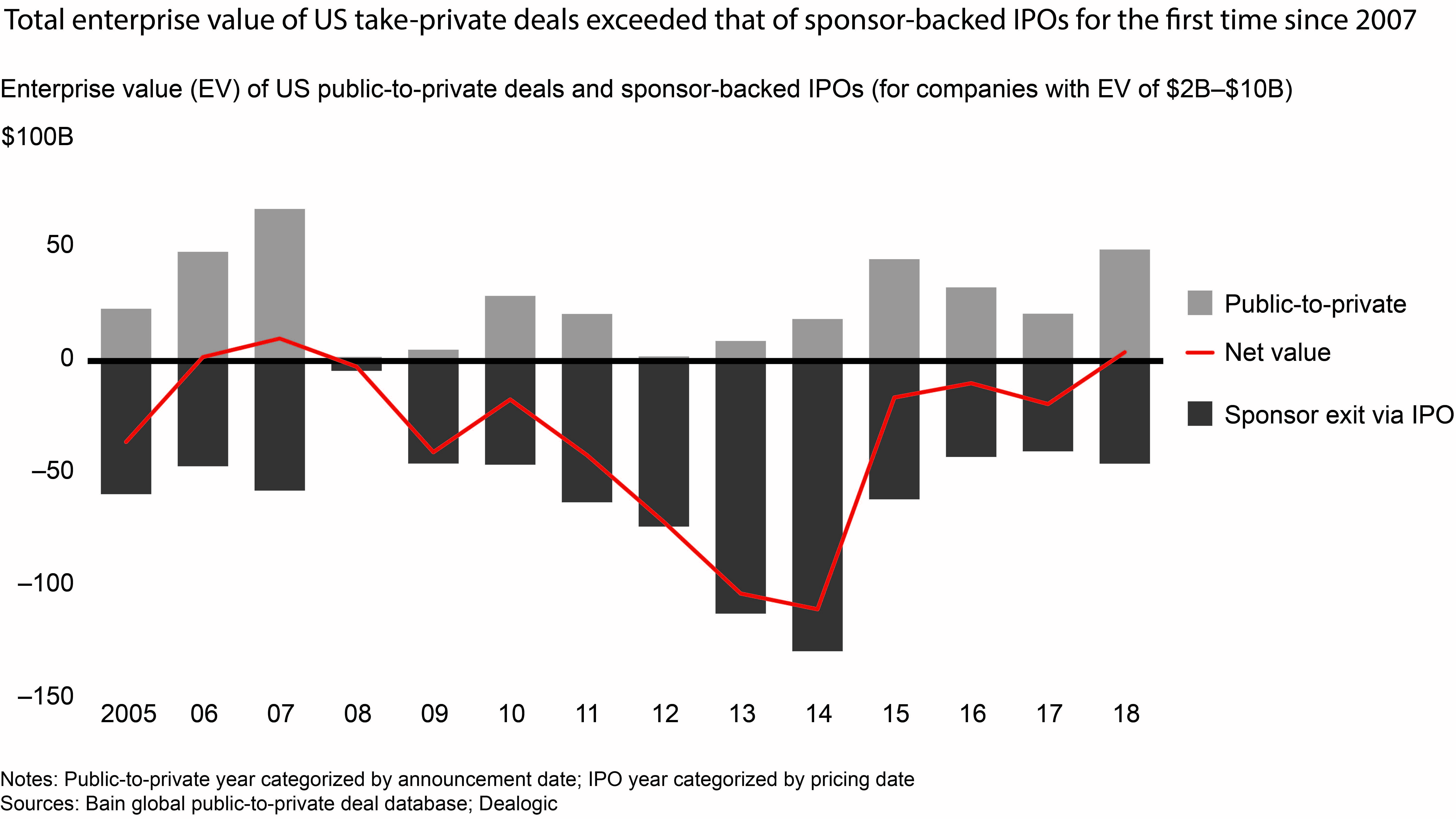

Meanwhile, the pool of companies ripe for take-private transactions has doubled since 2013. We define these as companies with an enterprise value between $2 billion and $10 billion that could be purchased for a multiple plus take-private premium that is still below the average private-market multiple. It’s unsurprising, then, that P2P activity is robust. The value of US companies going private in 2018 exceeded the value of those going public, causing a net outflow from public markets (see figure).

What would it mean for PE firms and their investors if private multiples remain elevated over the long term? We see several implications.

- Goodbye, IPO exits. At a minimum, it becomes less attractive to exit via an IPO. For GPs, the best prices for assets would increasingly come from selling a company to a strategic buyer or to another PE firm.

- Public company targets. The growth in P2P transactions could be just getting started. As public markets become a more important hunting ground, firms will have to shift their approach to deal sourcing, screening and due diligence.

- Even bigger megafunds. Recent launches by Apollo, Hellman & Friedman and Carlyle of $24.7 billion, $16 billion and $18.5 billion, respectively, signal that megabuyout funds are on the rise. We may see funds hit the $40 billion, or even $50 billion, mark.

- Democratization of private equity. A shift from public to private would accelerate the movement to make private equity more accessible to retail investors. Firms are already developing vehicles to tap the retail market. At Blackstone, for instance, 15% to 20% of annual fund-raising now comes from retail investors.

One thing’s for sure: As deals and funds get bigger, firms need to understand that a playbook for a $20 billion acquisition is not a simple “scale up” of the playbook they use to unlock value at a $2 billion company. Megadeals require a mega-investment in due diligence and the skills needed to choreograph change on a massive scale. From corporate-style M&A strategies to zero-based redesign to complex cultural change initiatives, firms will need to build their value-creation muscles.

The ascendance of private capital promises a bright new era for the private equity industry. But that doesn’t mean the road ahead will get any easier.