SOT NII: Harmonisation hits a floor of heterogeneity and here’s how to fix it

Executive summary

Supervisory Outlier Test on Net Interest Income (SOT NII) – i.e. European Union’s regulatory threshold for allowed bank’s NII sensitivity – is now effective for over a year. The evolution of the Interest Rate in the Banking Book (IRRBB) framework continues and one of the considered changes is a recalibration of stress scenarios underpinning the SOT measures. In this paper, we provide practitioners’ evaluation of SOT NII on its 1st anniversary, sharing our opinion on its flaws and unintended consequences it may induce. We explain why the proposed recalibration of stress scenarios would further exacerbate identified shortcomings, materially distorting the NII management among European Union (EU) banks. Finally, we explore several potential alternative evolution paths for the SOT NII framework, currently under discussion among EU Asset Liability Management (ALM) practitioners (Treasury & Risk). We also share our perspective on which of the options appears the most effective in ensuring the long-term IRRBB resilience of EU banks.

About the authors

Konrad Kompa is Director of Balance Sheet Risk Management at mBank SA. Jacek Rzeźnik is Deputy Director of ALM Risk Management at mBank SA.

Notes from the authors

The authors would like to express gratitude to several senior EU ALM executives for their peer review of the article and sharing valuable insights about SOT NII impact in the markets they operate in. In particular, we would like to thank professor Moorad Choudhry from London for his review and kind endorsement of this article:

“An excellent critique. Accessible, succinct and presenting practical solutions that will improve the IRRBB management process. Exactly what the market needs whenever it is evaluating any aspect of banking regulation. Good job!"

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the official position of mBank SA.

Contents

- Introduction

- An evaluation of SOT NII for its intended outcomes and effectiveness

- Possible solutions for the EU IRRBB framework and the way forward

- Concluding policy recommendations

- Appendix – a list of parallel shock changes per currency

Introduction

Complex and non-proportionate rules can hamper efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, it is important to scrutinise the framework and to revisit where policy products no longer deliver the intended outcomes.

These two sentences are actually not authors’ views, but words used by Mr. Jose Manuel Campa – the Chairperson of European Banking Authority (EBA) – used in his response to a broad call for deregulation.

In this paper, we provide scrutiny of SOT NII, a new regulatory metric hastily implemented following a 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which was caused by mis-management of IRRBB. The purpose of this paper, however, is not to pass judgment, but merely to offer practitioners’ insight that might help with arriving at a better policy outcome.

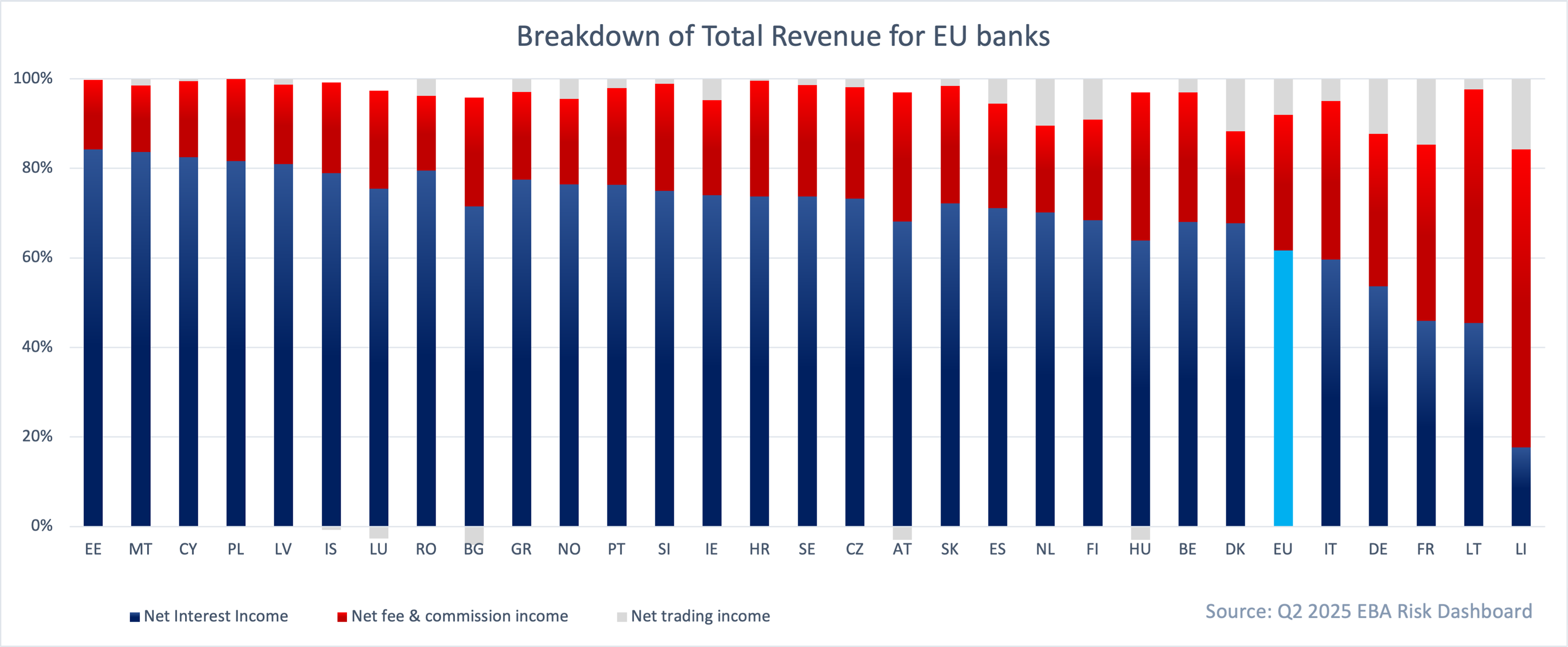

On the 1st anniversary of SOT NII, we share our candid thoughts on how it is already distorting the way EU banks manage interest rate (IR) risk. Whilst there are some noticeable differences between EU countries when it comes to banks’ reliance on NII (see Chart 1), naturally NII is the key revenue driver. Therefore, the policy that redefines how banks manage NII is essential to ensuring the resilience and competitiveness of the EU banking sector and must be robust and well-founded.

Chart 1: Total revenue breakdown into NII, NFC (Net Fee & Commissions) and NTI (Net Trading Income).

Evaluation of SOT NII

Intended outcomes

To evaluate SOT NII we need to start with defining its intended outcomes. These have roots in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) IRRBB framework: “a bank should be considered an outlier if (…) earnings are such that the bank may not have sufficient income to maintain its normal business operations.” Upon the introduction of SOT NII Regulatory Technical Standards the EBA also stated that “an objective is to inform supervisors about the exposure of institutions to IRRBB by obtaining comparable information for all institutions.“ Both those objectives are entirely reasonable. They’re examined in further detail below.

During the consultation period EBA considered two variants of SOT NII. Capital related metric (with Tier 1 in denominator) and income/expense related metric (being a function of administrative expenses). For the capital metric EBA rightly pointed out that “The metric does not show whether the post-shock NII can sustain normal business operations nor whether it is actually positive”. Nonetheless, EBA decided to choose this metric for “simplicity and comparability purposes”. This corresponds to efficiency mentioned by Mr. Campa, but doesn’t it come at a cost of effectiveness? We’ll explore a trade-off between the two.

Summarising, in this section we’ll evaluate SOT NII in the following 4 dimensions:

- Test for sufficient earnings

- Comparability

- Simplicity

- And – most importantly – effectiveness as a prudential tool.

The numerical examples we provide are based on our home market – Poland – yet the examined patterns and issues apply universally across the EU.

Test for sufficient earnings - one size fits all, does it?

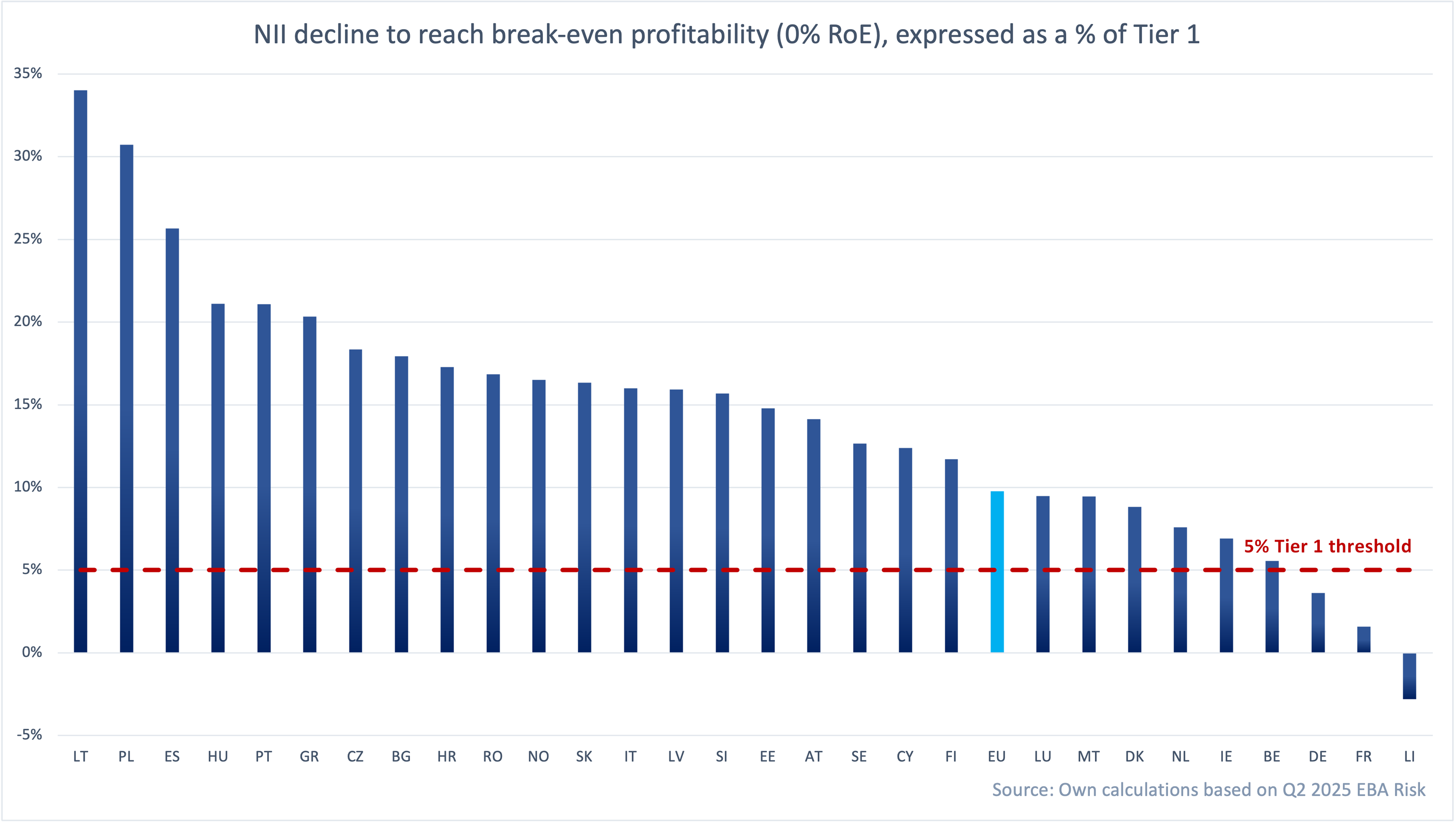

EBA places significant value in harmonisation, as a means of achieving resilience, improving efficiency and ensuring a level-playing field. The EU banking sector however, is quite heterogeneous, when it comes to business models, a tilt towards NII vs. NFC, fixed vs. floating rate lending practices, the overall profitability, cost structures (e.g. dense branch presence vs. online only), etc. Does setting the SOT NII threshold at 5% of Tier 1 (i.e. maximum allowed level of post-shock NII decline) align with regulatory intentions? Charts 2 and 3 illustrate why we think it does not (below).

Chart 2 illustrates the level of NII decline (expressed as a percentage of Tier 1) that would push a given banking sector beyond a point at which NII & NFC are no longer sufficient to cover Operating Expenses. This shows how big of a cushion each banking sector has when it comes to the NII volatility. For France and Germany, it’s less than 5% of Tier 1. For Lithuania, Poland, Spain and many other countries it’s more than 15% of Tier 1. EU average is close to 10%.

Chart 2: NII decline to break-even (0% RoE) as a % of Tier 1

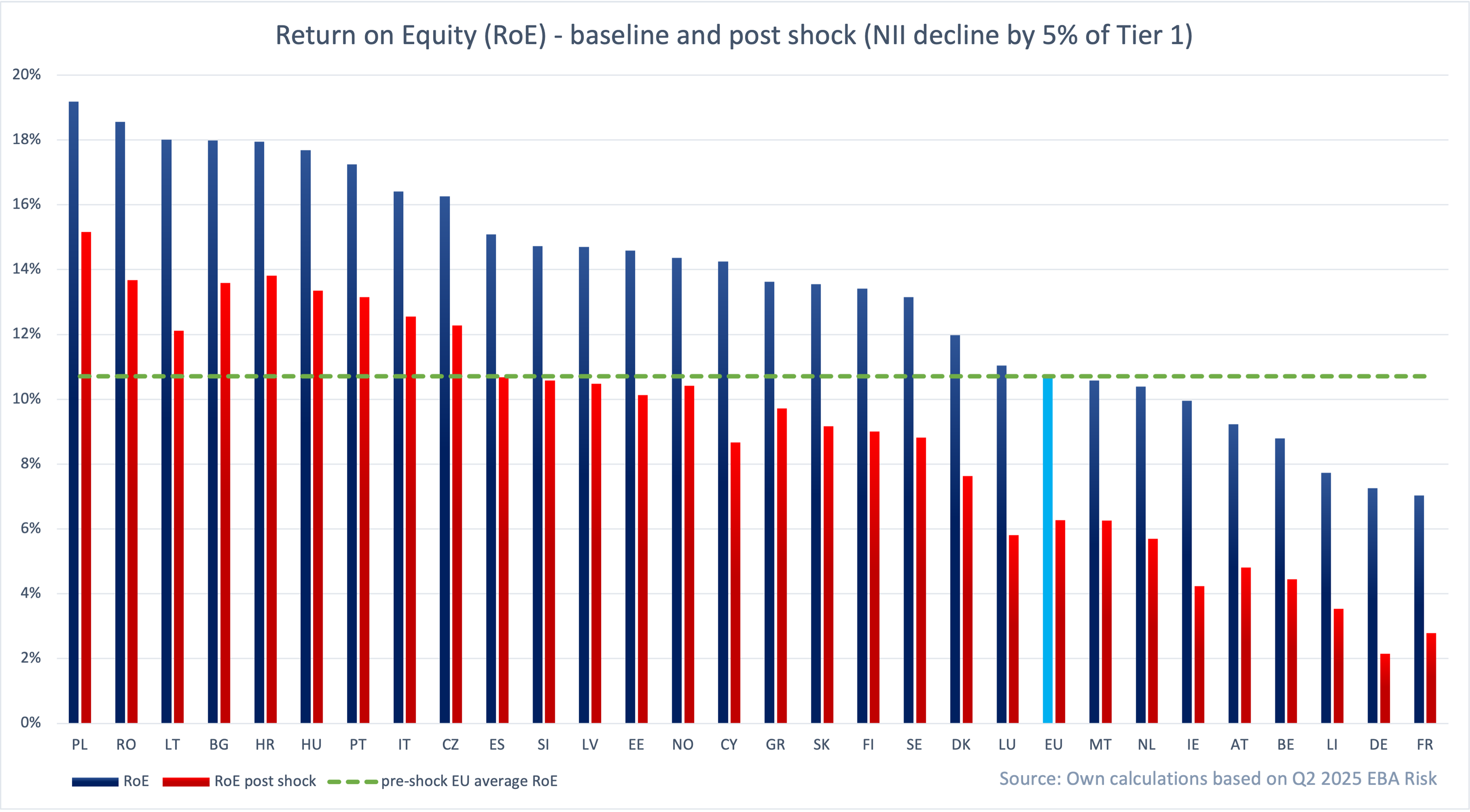

Chart 3 shows Return on Equity (RoE) numbers from the Q2’25 EBA Risk Dashboard and our estimates of RoE following a drop in NII (a 5% of Tier 1 drop). For 9 countries post-shock, RoE is larger than pre-shock EU average RoE. Those countries include Czechia, Italy, Portugal and Croatia.

Chart 3: Baseline and stressed RoE

The limitations of the current SOT NII metric are evident when considering the diversity of banking models across Europe. As Senior IRRBB Expert (ING Nederland) observes, “The current metric definition (delta NII/Tier 1 capital) may not be suitable for all business models/balance sheet types across the industry or different countries.” This highlights the need for a more nuanced approach that reflects the realities of different banking sectors.

We therefore conclude that SOT NII fails as a test for sufficient earnings. We’re left with 3 other objectives to explore.

Comparability? No thank you, not at all costs

Now, to make our point, we’ve got to delve a bit into mechanics of SOT NII. We’ll guide you through the next two more technical paragraphs.

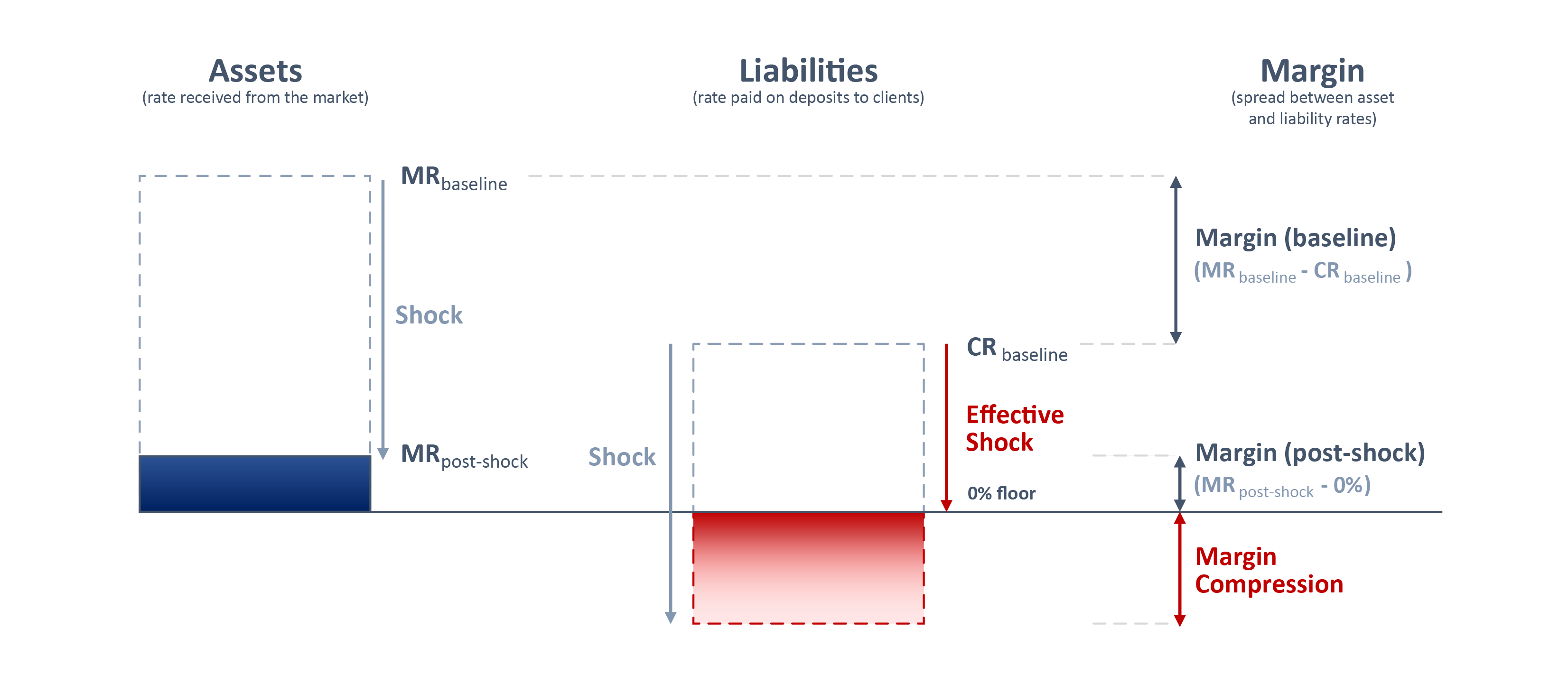

Let’s consider a hypothetical bank, with retail and corporate deposits on the liabilities side of its balance sheet. Let’s assume this bank has perfectly tenor-matched assets on the other side. Assets earn Market Rate (MR). Deposits cost Client Rates (CR). Bank’s NII, on this part of the balance sheet, equals to MR-CR. Following a downward shock, assets pay less i.e. MR – shock and deposits cost less, i.e. CR – shock (floored at 0%, assuming the bank doesn’t charge clients for deposits). As long as rates are high (high point of IR cycle) everything moves in tandem. Reduced income is offset by lower costs and there is no SOT NII impact (IR risk is closed). However, when rates are low (low point of IR cycle), with the 0% floor on deposits, the shock to the income side is not fully offset by lower deposit costs. As a result, the “margin compression” effect transpires, introducing asymmetry and driving SOT NII utilisation. See Chart 4 below. Why do we bother about that?

Chart 4: Margin compression effect

Let’s illustrate this effect with the Polish banking sector as an example. Based on the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (FSA) data the sector has around 1.5tn of PLN deposits and 232bn PLN of Tier 1. In the current rates environment, our estimate shows that utilisation of SOT NII driven just by margin compression on those local currency deposits is ~4% of Tier 1. This leaves hardly any space for the margin compression on foreign currency deposits, any IR mismatches or the balance sheet fluctuation.

In the absence of alternatives, especially on Current Accounts (that have CR = 0%), banks are incentivised to manage their margin compression by extending duration of assets beyond the 1Y observation window of SOT NII.

In other words, banks are led towards overhedging. Interestingly, the lower the baseline scenario market rate (i.e. the closer the 0% floor is), the stronger the margin compression effect. Our estimate for 2.5% MR gives SOT NII at the level of 5.5% Tier 1, just on PLN deposit margin compression. This means that the lower the prevailing rates, the more IR stabilisation SOT NII indicates. This is against common sense and a “yellow card” for the effectiveness objective.

What concerns us the most however, is that the margin compression effect also applies to unstable deposits. In our view SOT NII cannot incentivise banks to stabilise NII on unstable funds. That’s exactly what SVB did. We pointed that shortcoming to EBA via a Q&A back in 2023 (Question ID: 2023_6830), suggesting how to overcome that problem.

In 2024 we’ve carried out further analysis. We’ve run what-if scenarios for the Covid and post-Covid period, for the Polish banking sector, assuming that banks hedge SOT NII to 4.5% throughout the period.

During the pandemic, unprecedentedly low interest rates led banks to stop paying on Term Deposits and Saving Accounts. This, as a consequence, disincentivised clients to use these products, resulting in a growing overhang of unstable funds on Current Accounts. This phenomenon was further amplified by the Covid support programme, i.e. money handouts to small & medium enterprises and corporates. Based on National Bank of Poland (NBP) data and own estimates, between Q1’20 and early 2022, retail Current Accounts within the Polish banking sector grew by 24% and corporate Current Accounts by a staggering 45%. In Q1’22, upon the Russian aggression on Ukraine, we experienced unprecedented IR hikes, devaluation of bonds in banks’ High Quality Liquid Asset (HQLA) pools, collateral calls on IR Swaps and, to a lesser extent, physical cash hoarding by clients, especially in Eastern Poland.

As a result, the Current Accounts overhang of unstable funds started to reprice, migrating to interest paying products, or other banks. If margin compression on this cash overhang had been hedged (to 4.5% of SOT NII) the economic losses on those hedges would have exceeded 100% of Tier 1 of the entire banking sector. The tenor of assumed hedges was very short, just 1Y. This shows that the shortcoming we’ve identified can pose a systemic risk – even before the potential recalibration of the shocks. We’ve shared results of those analysis with EBA.

In 2025 IRRBB Heatmap EBA states that “In view of some concerns raised by the industry, the EBA has worked to provide a clarification on the expected treatment to modelling commercial margins of NMD [Non-Maturing Deposits] in the SOT on NII.” EBA conducted a QIS on this matter, which revealed that whilst according to EBA’s previous guidance “commercial margins should be scenario independent to avoid overlap with other risks – i.e., CSRBB or business model risk” only 38% of institutions use constant margins. The remaining 62% do not. EBA decided not to aim for harmonisation in this area. Instead, drifting away from the constant margins assumption, EBA suggests that for NMDs in the SOT NII banks should use the same modelling assumptions as in their internal systems, unless they don’t model margins. In the latter case banks should apply constant margins.

This means that SOT NII numbers today are not comparable and EBA decided not to aim for their comparability. Given the significant material impact of NMDs on the final numbers (acknowledged by EBA in the Heatmap), in our view SOT NII fails in the second category – comparability.

Simplicity & effectiveness: Does the capital related metric strike the right balance between efficiency and effectiveness in the end?

In the same 2025 IRRBB Heatmap EBA concludes that assessing IRRBB exposures and modelling NMD is very challenging and complex. Quoting EBA:

“It is highly complex to assess IRRBB exposures and management for the purpose of assessing the need for supervisory measures and, in particular, to ensure a minimum common understanding of such holistic analysis across supervisors and institutions in the EU.”

“The inherent characteristics of NMD make their behavioural modelling for repricing purposes complex to assess and manage.”

If we add on top the new requirements to develop commercial margin evolution models (EBA suggests, for example, modelling lags in NMD pass-through rates) we’re ought to pass a negative verdict on the simplicity objective as well.

Concluding our evaluation of SOT NII, it does not fulfil any of the three analysed objectives and on top of that it generates side effects (incentivises stabilising NII when rates are low, potentially increasing risk instead of mitigating it – to name the key). We therefore conclude that SOT NII is not an effective prudential tool.

Possible solutions for the EU IRRBB framework and the way forward

Alert, alert! Hazard ahead detected

The purpose of this paper is not merely to provide a summary of the status quo. Rather, it aims to draw attention to these critical concerns in light of the forthcoming changes, which are expected to further exacerbate the challenges outlined above. In July 2024, Basel released an updated recalibration of IRRBB shocks, with implementation set to begin in early 2026. Apart from updating the observation window, Basel changed key methodological assumptions:

- increasing the confidence level from 99th to the 99.9th percentile – increases conservatism to account for tail risks i.e. more severe but plausible shocks

- deriving local shocks specific to each currency – moving away from a uniform methodology and allowing for a more tailored reflection of individual currency interest rate dynamics.

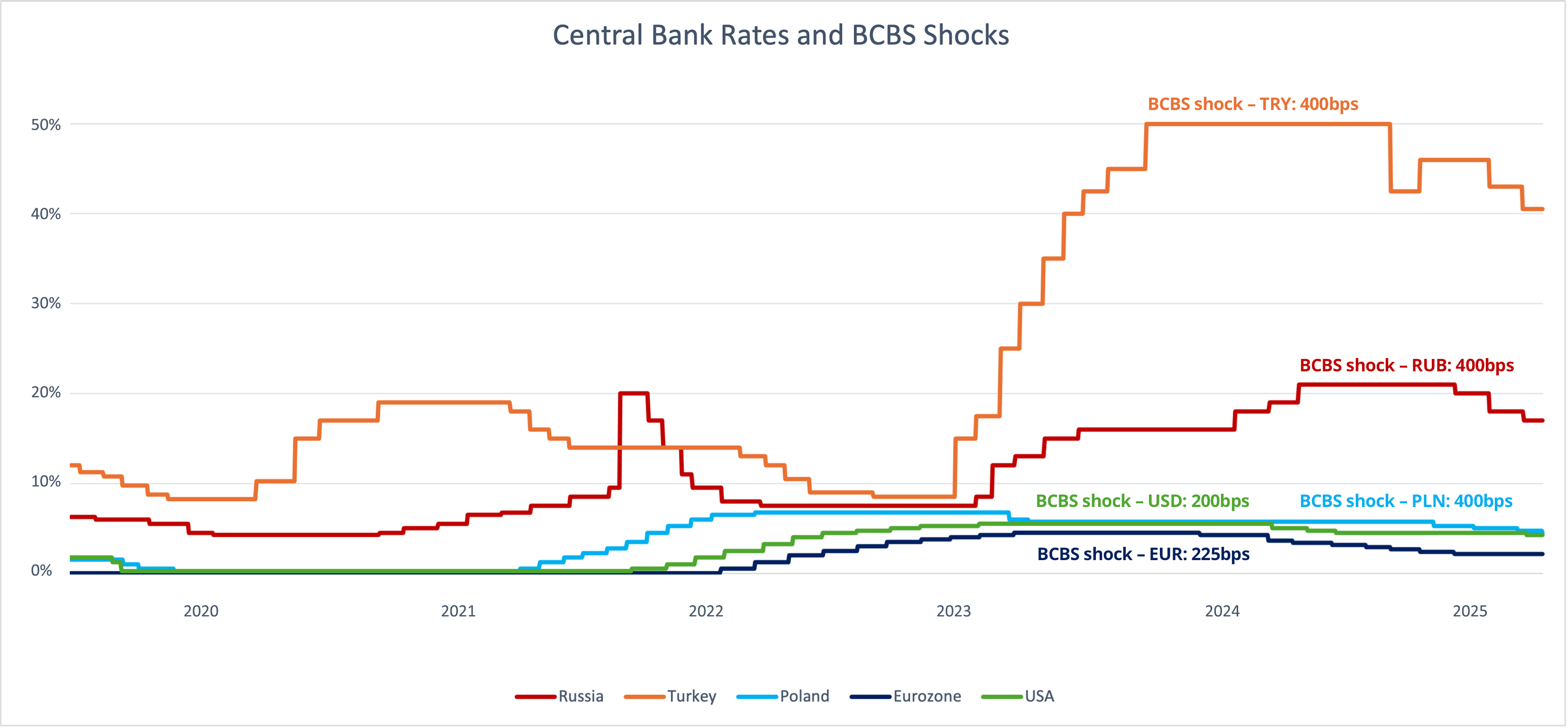

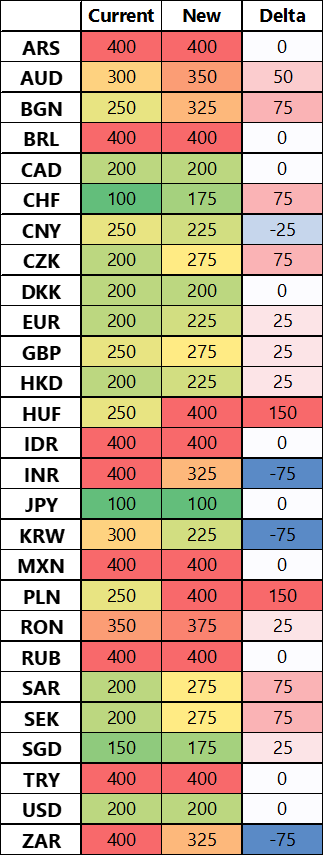

The recalibration results in substantial increases in shock sizes for several currencies. For example, HUF and PLN experienced 60% increases from 250bps to 400bps, whilst CZK, SAR, and SEK saw increments of 75bps to 275bps, and CHF increased by 75bps to 175bps (see Appendix for the full list). Notably, the increase to 400bps for PLN aligns it with shocks applied in such volatile IR markets as TRY and RUB, which, as depicted in the graph below, exhibits very different interest rate dynamics.

Chart 5: History of interest rates for selected currencies

Higher shocks mean banks will need to reassess behavioural assumptions, deposit modelling and hedging strategies. However, it also leads to more restrictive (Economic Value of Equity (EVE) and NII metrics, which narrows the regulatory corridor between SOT EVE and SOT NII, i.e. the effective space left for banks for their IRRBB discretion.

This clearly limits banks’ flexibility and diversification of strategies, especially the NII stabilization strategies. Proposed change of shocks is much larger for non-EUR currencies, compared to EUR. The higher the historical interest rate volatility for a given currency the narrower the regulatory corridor for managing the balance sheet.

This also goes against the risk management intuition. Countries with higher interest rate volatility will naturally have higher NII volatility and thus should have wider NII volatility thresholds (as long as this does not endanger their operations, of course). Considered recalibration of SOT NII shocks would distort NII management in non-EUR jurisdictions to a larger extent than at Eurozone banks.

Repeating the same estimates as above for PLN deposits, but for 400bps shock, indicates 8.8% SOT NII for current MR and 11% SOT NII for 2.5% MR. In other words, based on our estimates, if shocks were recalibrated the entire Polish banking sector would become an outlier. We’ve also run analysis what spillover effects this would have for the liquidity risk management framework.

At the end of H1 2025, the Tier 1 capital of the Polish banking sector stood at PLN 257bn, based on Polish FSA data, setting the regulatory SOT dNII threshold (5% of Tier 1) at PLN 12.8bn. Currently, a 250bps shock allows banks to keep PLN 512bn of assets marked to overnight (O/N). Raising the shock to 400bps would cut this capacity by half, down to PLN 320bn. This is an illustrative simple example assuming funding with non IR sensitive 0% rate deposits. Polish banks' ability to hold short-term overnight assets would be reduced by 37.5%, requiring them to invest the remainder in assets with maturities longer than one year.

This would effectively introduce a new limit on the composition of banks’ liquid buffers, necessitating longer durations of HQLA. (At the end of H1 2025, based on Polish FSA data, LCR net outflows for the sector stood at PLN 510bn, which means little more than half (63%) of liquid assets for LCR compliance could be kept in short term O/N placements.)

This may lead to broader balance sheet changes e.g. altering asset allocation or funding sources. Furthermore, this may also lead to making uneconomic decisions, such as investing in non-interest-bearing assets (e.g. cash, bitcoin, gold), increasing reliance on more expensive wholesale funding, or seeking more price-sensitive deposits.

Consequently, we are concerned that banks will encounter increased pressure to take on greater risks, potentially resulting in unintended consequences. As a risk manager from a European bank cautions, “NII SOT may push institutions toward potentially overly defensive and economically unjustified hedging strategies in a low-interest-rate environment, especially in light of the recalibrated shocks.”

Whilst the elevated interest rates environment mitigated some of the dangers associated with over-stabilizing NII, larger shocks and the impact of deposit floors will compel banks to further stabilise during periods of low interest rates merely to avoid breaching the SOT NII threshold.

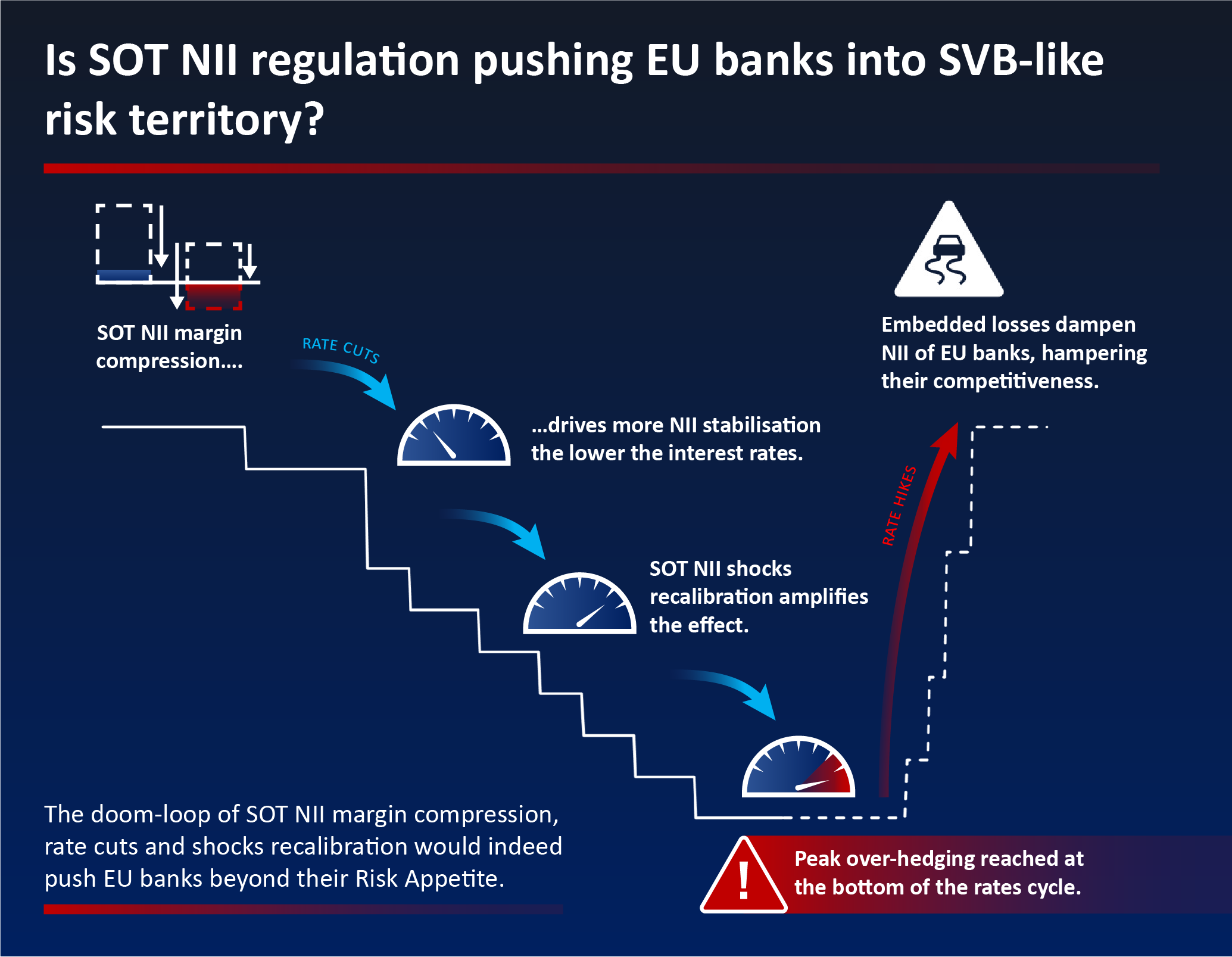

Given the significant consequences of this strategy in an environment of rising rates, we do not regard this approach as a prudent one. Furthermore, we believe it does not align with the intended objectives of the IRRBB regulatory framework. Chart 6 (below) illustrates how the doom-loop of SOT NII margin compression, rate cuts and shocks recalibration would push EU banks beyond their risk appetites, towards SVB-like risks.

Chart 6: The doom-loop of margin compression, rate cuts and shocks recalibration

Don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions

We held numerous discussions with ALM managers and ALM risk managers across the EU, aiming to capture industry views on how the EU IRRBB framework could be improved. We’ve also studied EBA’s exchange with European Commission (EC) from 2022/23 (that resulted in a threshold change from 2.5% to 5%) and BCBS papers from 2014–2016 when the committee considered putting IRRBB into Pillar 1 (but in the end concluded that it’s best suited for Pillar 2). In this section we synthesise industry feedback we’ve gathered, presenting it in the context of EC and BCBS conclusions and add our own subjective view on possible paths forward.

From 2014–2016, the Basel Committee considered moving IRRBB to Pillar 1 with a mandatory capital charge but opted to keep it under Pillar 2 due to diverse bank profiles and practices. Following a broad industry debate, the committee concluded that implementing a standardised approach was impractical and potentially disruptive. Despite officially being Pillar 2, the current NII SOT framework includes several Pillar 1 elements – such as quantitative standards and standardised EVE or NII reporting – for comparability. Whilst there’s no formal capital charge, outlier banks may face sanctions including add-ons, creating an indirect link to Pillar 1.

In the early 2023, in response to changes proposed by EC, the EBA proposed increasing the threshold from 2.5% to 5%, stating that it was set in response to “current exceptional circumstances” and that EBA will monitor the impact of the new regulations, particularly in relation to changes in interest rates and banks' balance sheets. The authority then stated that it is prepared to review both the threshold level and the methodology if necessary, including revisiting the definition of a "large decline", should additional information become available or when market conditions change.

Concerns have been raised within the industry about the current SOT NII threshold calibration. As Senior IRRBB Expert (ING Nederland) aptly supports, “I believe the calibration methodology lacks a sound conceptual or economical foundation.” This highlights the urgency to enhance and refine this process. Given SOT NII complexities outlined in this paper, and the changed interest rate environment, in authors’ view it is now high time for EBA to act upon the pledge mentioned in the previous paragraph, i.e. to review and consider further changes to SOT NII. Below we outline several possible options for improving EU’s IRRBB framework.

Option #1: the least the stability of the banking sector deserves

Given all the outlined shortcomings and the change in the shocks’ percentile, the least the industry expects is a review and recalibration of the SOT NII threshold. Whilst we fully support this request, we think it’s not the best of possible ways forward, as it does not address the aspect of heterogeneity. As long as the EU banking sector remains diverse, a one-size-fits-all threshold will not be feasible. Under this approach SOT NII will also not serve as a test for earnings sufficiency, which in our view is key.

Option #2: Was EC right upfront about heterogeneity?

In the aforementioned exchange between EBA and EC, the commission made a proposal that accounted for the heterogeneity issue. EC suggested that local supervisors should rank banks under their supervision by NII decline and select a sample with the largest declines that is proportionate to the sample of EVE outliers. In this sample, banks with NII decline of 2.5% of Tier 1 or more, would be deemed outliers. This more country specific approach would be better suited to reflect the heterogeneity of the EU banking markets. In our view, applying jurisdiction-specific thresholds would be a step towards the right direction, however we’re not convinced that calibrating SOT NII to the number of SOT EVE outliers is the best approach, as it lacks practical meaning from the bank’s stability perspective.

Another potential alternative would be adopting currency-specific thresholds, which would enable the framework to more accurately accommodate the diverse banking models and differing interest rate conditions prevalent across the EU.

Option #3: An idea for better comparability

Another option we’ve heard about would be to set a single threshold and standardise the shock size across all the currencies, e.g. at a 200bps level. This approach would ensure consistency and provide comparability among institutions operating in different currency zones, making it easier to benchmark the results. However, this is not our preferred option, given the heterogeneity present across the EU banking markets. Our analysis indicates a preference for a more country-specific approaches.

Some other practical solutions proposed by a Head of Balance Sheet Risk Management from a leading CEE & SEE banking group include:

“Allowing a portion of the shock to be gradual over a short time horizon (rather than fully instantaneous) for NII SOT purposes.”

“Test the banks with different shocks, e.g. in 50bps increments”

“Calibrating shock sizes depending on the current interest rate environment – the lower interest rate levels would automatically trigger the lower shocks and vice versa…”

These approaches provide alternatives to consider when implementing shocks. Third idea corresponds to critique of SOT NII presented by the National Bank of Poland (NBP). In December 2024, Financial Stability Report NBP states: “An important drawback of the SOT NII is that it does not take into account the phase of the monetary policy cycle, which has a significant impact on banks' net interest income.”

Option #4: A change of direction is evidence of a decision-making process continuity

Some think EBA shall consider going beyond simple threshold adjustment and change the metric itself. Either by returning to the interest / expense-based metric, as it’s more meaningful, or perhaps consider changing SOT NII denominator, from Tier 1 e.g. to NII. Others say that finding a one-size-fits-all interest / expense-based metric would be even more complex than for the current capital metric and hence strongly oppose this option. Whilst the interest/expense metric is more meaningful for us, we share concerns about opening yet another Pandora’s box of complexity and see other, broader reasons why we don’t think it’s the best way forward.

Option #5 (recommended): Prescribing painkillers for a broken bone & Goodhart’s law

In our view, a pertinent observation by a British economist Charles Goodhart encapsulates the challenges troubling the current SOT NII framework: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. Initially conceived as a supervisory benchmarking tool under Pillar 2, SOT NII has, in practice, evolved into a de facto regulatory limit. This shift has prompted banks to adopt a defensive stance, prioritising avoidance of regulatory or reputational repercussions over the intended early warning function of SOT NII.

Acknowledging SOT NII imperfections, as a remedy, EBA prescribed that “no automaticity” in sanctioning outliers should apply in the event of a breach. Given that SOT NII does not indicate if bank’s NII risk is excessive, EBA also defined a set of complementary measures to facilitate assessment of outliers. In our candid view, these are just painkillers, targeting symptoms not the root cause.

The list of potential sanctions for breaching SOT NII is the same as for breaching Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) or Total Capital Ratio (TCR). It’s defined in Article 104 of Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) and include, among others, restricting business, additional capital requirements and limitations on shareholder distributions. Given the heavy-weight of potential sanctions, it is difficult for institutions (Management Boards, Supervisory Boards) to accept a lasting SOT NII breach. It would also put local regulators in quite an uncomfortable spot, if e.g. entire banking sector in a given country was in breach.

In September 2025, “a senior risk manager at a European bank” stated in a Risk.net article that they “were expecting more outliers at the go-live than we have seen, but think there was a general tendency for banks to see that as a hard limit coming in.” We’re not surprised by that. Management’s acceptance to breach regulatory thresholds would also be detrimental to the risk culture, which is a backbone of the risk management profession and foundation of banks’ resilience. An ability to safely comply with a metric should be an inherent characteristic of all regulatory measures. Regulatory measures should not push banks beyond their risk appetite.

Regarding the complementary measures – they are helpful, but the Pillar 3 disclosure regime further compounds the issue by exposing outlier status to market participants, potentially leading to misinterpretation of complex IRRBB risks and negatively affecting bank’s reputation. Having analysed EU banks’ disclosures we also see that some banks might have been incentivised to take suboptimal risk positioning to avoid breaches. Following the implementation of SOT NII, some banks started entering the so-called ‘pivot positions’, i.e. they overhedge the 1Y window, on account on underhedging tenors >1Y, exposing them to risk which we assume they would not otherwise have taken. As outlined earlier, these unintended consequences are going to worsen in low-rate environments and under new stress scenarios.

Having analysed the topic in depth, in our view, the best way for the EU IRRBB framework would be to reposition SOT NII status to a genuine risk indicator, by removing the prescribed 5% Tier 1 threshold. This would enable a more proportionate and context-sensitive supervisory response, supporting the use of SOT NII as a bespoke tool for bilateral assessment between banks and supervisors.

By implementing a tailored, risk-sensitive approach — modelled on the spirit of the Pillar 2 framework and adaptable to national and institutional specificities under the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) — EBA can restore SOT NII’s intended purpose, improving regulatory frameworks efficiency at the same time.

Such a change would reduce misleading breaches, foster prudent risk management, and ensure that regulatory measures are both proportionate and targeted, ultimately strengthening the resilience and credibility of the EU IRRBB supervisory regime.

Concluding policy recommendations

With profitability, resilience and competitiveness of EU banks at stake the minimum that is required, upon the introduction of new BCBS shocks, is a recalibration of the SOT NII threshold. This however, as we explained, will not result in a level-playing-field across the EU. In some countries the risk of excessive NII volatility will remain overlooked below the threshold, whilst elsewhere the margin-compression overhedging at the bottom of the interest rates cycle will erode shareholders’ value. We therefore urge EBA to act decisively, by moving beyond a one-size-fits-all threshold concept towards a framework without a predefined regulatory target level for SOT NII. Fully effective and comprehensive SREP assessment of IRRBB risks can be done without the SOT NII threshold.

Maintaining the status quo is not a viable option; to do so would risk entrenching existing flaws in the framework, exacerbating vulnerabilities as interest rates fall, exposing EU banks to unnecessary risks, and undermining confidence in IRRBB oversight. It is crucial to recognise that the decisions on SOT NII will directly influence the IRRBB risk profile of the banks across the EU. These are not technicalities, but foundational choices that will shape the EU banking sectors’ profitability for the years to come. The importance of getting this right cannot be overstated.

Now is the time to act, ensuring that the IRRBB framework remains robust, proportionate, and fit for purpose. We invite all of the industry stakeholders (including EBA) to engage collaboratively in this process. We also genuinely hope that EBA will find observations and ideas presented in this paper useful.

Discuss these challenges with 1,200+ risk leaders at RiskMinds International this November!

Appendix – a list of proposed parallel shock changes per currency

Table 1: Comparison of current and new BCBS shocks.