The US-China trade war may cause multipolarity instead of deglobalisation

Did we cry deglobalisation too soon? Our fear of deglobalisation is valid but it seems that the US-China trade war has a different impact on the global economy and trading practices. Henri Kouam Tamto, Research Fellow at the Denis & Lenora Foretia Foundation, explains why trading relations are more resilient than you might think!

The US-China trade, technology, and possibly currency war suggests a continued escalation beyond rhetoric, with negative implications for trade in an already slowing global economy. Following the bout of tit-for-tat tariffs, talks of deglobalisation have emerged strongly, and the falling trade volumes between both countries undoubtedly support this narrative. Such claims, I think, are however misplaced as the unintended consequences of the trade war could incentivise rather than impede trade amongst other economies in Asia, Europe, and beyond. Furthermore, deglobalisation is possible only if all countries simultaneously engage in trade wars or if a Western-Eastern split emerges more strongly. Nevertheless, the aggressor i.e. the US is unlikely to impede trade amongst countries over the long-term, but the short-term economic costs cannot be understated. Falling PMIs, waning business investment, and stock market corrections in both Shanghai and New York suggest the reverberations of the trade war are increasingly palpable.

It might seem like economic nationalism could present significant headwinds to globalisation, but most of the world continues to trade and all indicators suggest Britain will actively pursue independent trade agreements with the rest of the world, contingent on the nature and the timing of its exit. Meanwhile, the European Union (EU) has signed a comprehensive trade agreement with Latin America, spanning a range of consumer and non-consumer products for both sides. Nevertheless, its adoption and successful passing in the European Commission is contingent on increased environmental awareness by Jair Bolsonaro, who views the Amazon as an economic anchor for the Brazilian economy.

Latin America and the EU are countering the deglobalisation trend

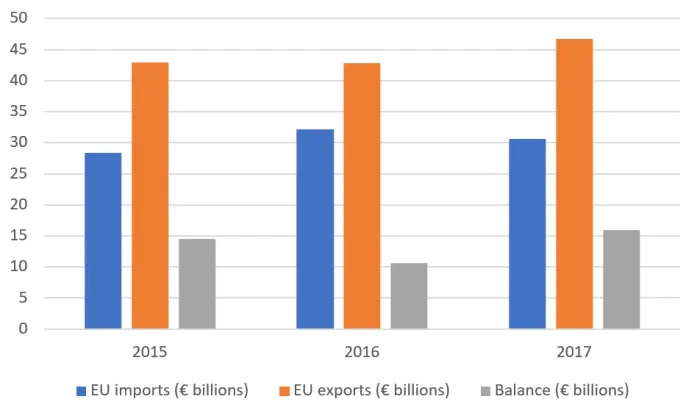

Following the election of US President Donald Trump and the resulting trade war, as well as Brexit, the EU has continued to champion free trade, negotiating an independent and comprehensive trading agreement with the Mercosur trading block. The latter comprises of a group of Latin American countries, namely Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Uruguay. It is important to emphasise significant levels of trade between both trading blocs; the EU currently exports €45 billion worth of goods and €23 billion worth of services. It is also the biggest investor in Mercosur with a stock of €381 billion and €52 billion from the Mercosur trading area. These numbers are likely to grow significantly with the removal of tariff and non-tariff restrictions over the coming years.

Before the recent trade agreement, investors were significantly constrained in Mercosur markets, but the recent agreement removes both tariffs and non-tariff barriers to enable and facilitate trade for smaller SME’s amongst both countries. Contrary to the US decision to exit the Paris climate agreement signed in December 2015, the agreement also strengthens workers’ rights, environmental protection, and food safety standards. This agreement is salient for member countries in Latin America, who are on the verge of an economic transition with a growing population and prospective middle class, which present significant opportunities for EU firms going forward. Whilst countries such as Peru seek to escape the middle-income country trap, Brazil and Argentina might benefit from EU market access as manufactured products comprise a majority of their exports.

Furthermore, domestic companies will also benefit from knowledge transfers and/ or exchange, which is ultimately transferred as countries become interlinked through trade. Not only will this improve the domestic competitiveness of firms in Latin America, but consumers will also be able to access technologically advanced products such as solar panel, electric vehicles, and climate technology. This is both paramount and indispensable if said countries are to leverage their climate and demographic transition. Although Brexit suggests less open trade with the EU, the United Kingdom is poised to pursue more pragmatic trade policy as its industries will no longer be shielded by comprehensive and wide-reaching EU trade agreements.

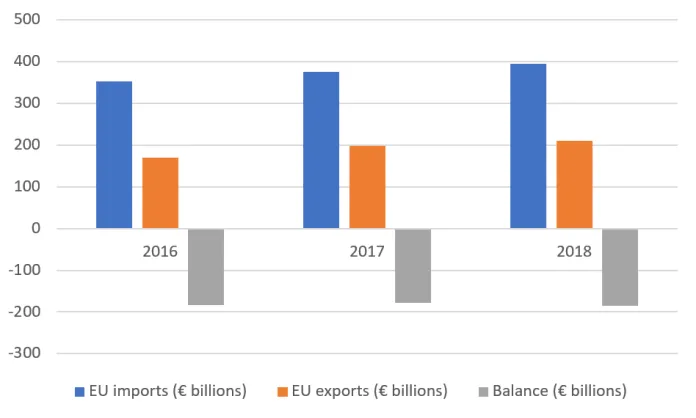

Figure 1: EU – China trade in goods is rising steadily (Source: European Commission)

The EU and China: trading and reforming simultaneously

The Trump administration imposed 25% tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese products, 10% on another $300 billion worth of Chinese imports into the US, and placed Huawei, a Chinese telecom on an entity list in an attempt to disrupt its supply chains and reduce its competitiveness and rapid expansion across the world. While the reasons for the trade war are not completely unjustified, his approach is diplomatically misguided and economically counterproductive for US companies. In spite of the many challenges and value differences that emerge from trading with China – for example, its unfortunate human record, forced technology transfers, subsidies and non-tariff barriers designed to protect domestic incumbent – the EU has opted for a more diplomatic and mutually beneficial approach; one which seeks to enhance the economic benefits of the trading relationship rather than simply mitigate China’s perceived market dominance in some sectors. China and the EU trade significantly with German cars, European planes, chemicals and equipment – all imported by China to support its trade, manufacturing, and competitiveness. Meanwhile, the EU equally imports clothing and footwear, industrial and consumer goods, and machinery and equipment to support more advanced manufacturing in Europe.

Furthermore, EU-China trade in services comprise 10% of total trade in goods and EU export of services make up 19% of EU total exports. The Chinese markets present significant opportunities for climate-technologies (solar panels, wind turbines, and storage technology), financial services, pharmaceutical, and agricultural products amongst others. Meanwhile, China can benefit from EU technological advancements, well-developed capital markets and a less hostile investment climate than the US, for example. Whilst the EU and other economies around the world grapple with the adoption of Huawei’s 5G technology, it’s important to maintain market access for EU and other firms in China’s consumer-centric market.

Figure 2: EU-China trade in services (Source: European Commission)

The EU’s trade with China is pragmatic, rather than driven by any set of ironclad values vis-à-vis the Uighur Muslims and recent protest in Hong Kong against an extradition bill. Despite trading significantly with China as illustrated in Figure 1 and 2, the EU designated China a strategic threat. By no means was this a deterrent for trade amongst both continents, but rather, it suggests an understanding of Chinese trade practices and its economic and foreign policy implications. The EU continues to negotiate with China to improve its industrial policies, state subsidies, non-tariff barriers against foreign companies, poor protection and enforcement of intellectual property, and strong government intervention in state-owned subsidies.

Tariffs don’t work

Rather than imposing economically counterproductive tariffs on Chinese products such as phones, technology, and climate technology to protect domestic companies, the EU is using diplomatic means to improve the trading relationship with China. Although social dumping justifies tariff and non-tariff barriers, in international trade, domestic industries who are most shielded from the external competition via tariffs tend to experience more pronounced adjustments when trade barriers are removed. This is a further disincentive for direct trade conflict or tariff war. Admittedly, domestic companies might momentarily benefit from trade restrictions, but the companies in the penalised country will seek new markets and redesign their supply chains to withstand future shocks. This stymies innovation and better-priced products for consumers, demands for intermediate product might fall between both countries. China, meanwhile, has imposed 5.0% tariffs on US autos and oil imports, due to take effect in September and December 2019, respectively. Furthermore, companies providing intermediate products or software to Chinese technology companies are unlikely to benefit over the near-term and they are unlikely to find markets willing or able to match demand from China.

UK and Africa are also choosing free trade

Meanwhile, former Prime Minister Theresa May toured Kenya and Nigeria with business leaders from the UK during her tenure to improve trade ties and support development in the most populous and the most technologically advanced countries on the continent. She also pledged a £4 billion fund to support youth employment, cultivating the industries and markets on which the UK will soon depend to sell Irish beef or the City of London’s consultancy and financial services. Although the decision to leave the EU suggests less open trade with the latter, the UK is nonetheless trading and will continue to do so, with other countries in the world.

Meanwhile, Africa is learning from the EU and recently tabled proposals to create a free trade area that will reduce tariffs on goods amongst countries, encourage trade, and spur development. The continent of 1.2 billion has cities with some of the fastest rates of urbanisation and will likely be the fastest-growing continent according to the UN. Not only will a free trade area facilitate the attainment of sustainable development goals by standardising trade and labour market practices, by sharing knowledge via competition, and by encouraging cross-border supply chains, it will also facilitate trade outside the continents and speed up development.

As the above trade agreement suggests, most of the world is becoming integrated and economically interdependent even as the US threatens or imposes tariffs on the rest of the world (i.e from Canada, Mexico, France, Germany, etc.). All indicators suggest the world is choosing to stay open and maintain the global rules-based order even as the current US administration seeks to chip away at its legitimacy. A Chinese or US dominated world is unlikely to become a reality at this point and greater economic interdependence among the rest of the world underpin this point.

The United States and China might be embroiled in a trade war for the foreseeable future, resulting in less trade in both economies. Even as the short-term economic costs cannot be understated, the long-term implication is much more nuanced than current claims of deglobalisation suggest. However, businesses in both countries will likely find new suppliers in new markets, which suggest a structural shift in global trade, but it is difficult to see how a retrenchment in trade between both economies suggests a broader trend of deglobalisation. US chip, semiconductor, and software producers might find new markets in rapidly industrialising countries in Asia and Latin America, while Huawei will continue to expand rapidly in other markets, not only providing phones but also the digital infrastructure which is indispensable for economies such as Brazil, Kenya and India, poised to grow at a much quicker pace than most industrialised nations in the coming decades. Furthermore, the jury appears to be out on 5G, but chances are, it will underpin the next wave of industrialisation. If the US chooses not to adopt 5G, it is almost certain that other countries would.

Trade will be cleared in all other currencies

It is easy to see how the current tariff dispute might result in deglobalisation of some sort, but this is the case for China and the United States rather than countries around the world. For emerging markets, China remains an invaluable market for commodity exports and more affordable Chinese products will continue to be purchased in other countries in the EU, North America, Latin America, and Africa. Furthermore, a likely result of the trade war is that trade, which was previously invoiced in the dollar will now be cleared in Euros, pound, Renminbi; a boon for the global economy and financial stability over the long run. Rather than focus on deglobalisation, the US – China trade dispute will incentivise multi-polarity in trade and investment whilst facilitating much-needed reforms to the multilateral trading system.

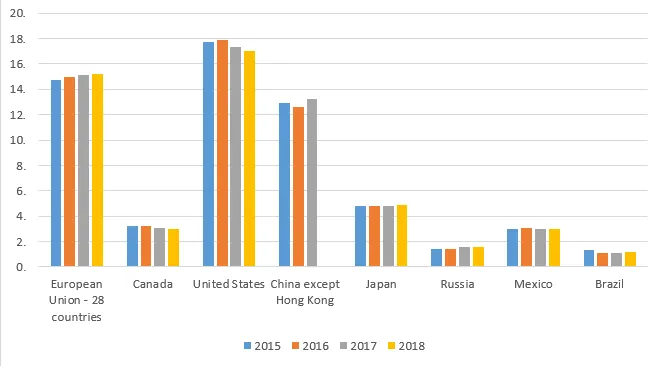

Figure 3: The world is still trading (%) (Source: Eurostat)

It is unclear that the dollar dominance has been positive for all countries

The dollar remains the dominant currency for global trade invoicing, and 2/3 of security issuances also occur in the greenback. This has left emerging markets exposed to dollar strength and global trade tends to fall when the dollar appreciates. Not only do high levels of dollar-denominated debt leave countries exposed to banking and currency crisis, but it also raises global financial stability risk. As a result of global trade being cleared in other currencies (see figure 3), this will lessen the dollar-induced crisis and bolster resilience amongst emerging market economies. As debt concerns become increasingly prevalent vis-à-vis dollar strength, a more globalised pool of funding and FX mix for debtor countries will not only reduce financial stability risks, it will likely improve the functioning of monetary policy.

A fortunate consequence of the US – China trade war is that global trade will be cleared in a range of other currencies ranging from the Chinese Yuan to the Euro and South African Rand. This trend is already becoming increasingly apparent; as the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates, capital flowed out of emerging markets, but was swiftly replaced by the Euro. We are likely to see countries diversify financing sources, more so as market-based financing plays an increasingly important role in funding EM current account deficits and financing needs. The trade war will have grave short-term costs, compounding the slowdown in the global economy, but a more multipolar world will be net-positive for economies around the world by improving funding sources and reducing the risk of a dollar-induced crisis. Companies such as Rosneft, a Russian oil producer, have already notified customers that future oil tenders will be conducted in Euros, reinforcing the argument for a more multipolar world in spite of the uncertainty surrounding the US – China trade war.

By no means am I discounting concerns of deglobalisation. I do, however, believe that trade amongst other economies around the world will lessen the risk of a prolonged trade war splitting the world into two halves. Given the size of the US economy, its impact on global trade cannot be understated, but the remaining 163 countries in the WTO will continue to trade even if the trade war diminishes the role of the dollar. One should, therefore, approach claims of deglobalisation with caution.

This article was originally published on Data Driven Investor.