Top Tips for Improving Competition Law Compliance Regimes

With our Competition Law Compliance conference fast approaching on September 27th, we thought it might be time to get an expert opinion on the topic at hand. We reached out to Kim Dietzel, esteemed partner and compliance expert, to talk us through the key stages of a successful competition law compliance regime.

With the European Commission imposing record antitrust fines (nearly €3bn in the recent trucks cartel alone), multi-million competition damages claims being brought as a matter of course, and young competition authorities flexing their enforcement muscles across the globe, competition law compliance is more important than ever.

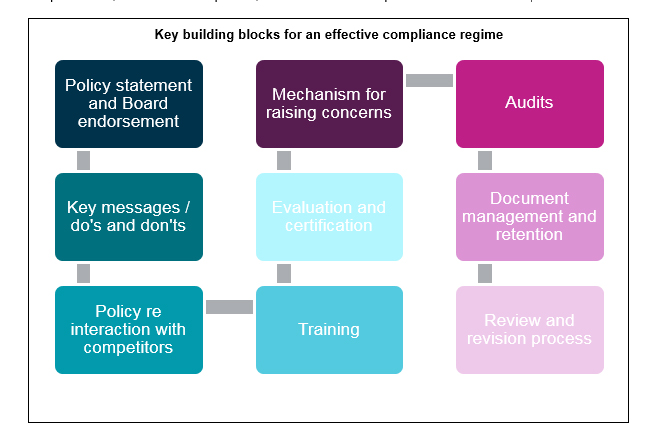

A competition compliance programme (see box for key elements of such a programme) cannot simply be a paper trail playing lip service to compliance. It must be effective in reducing competition law risk exposure, by creating a compliance culture, identifying potential problems before they arise, and enabling issues to be spotted and stopped early. Creating and maintaining an effective compliance regime is challenging for companies, in the face of limited resources, employee fatigue at training overload, and legal and cultural differences across jurisdictions. We discuss below our top tips for overcoming these challenges and implementing an effective competition compliance regime.

1: Enhance engagement

Effectively engaging individuals and getting them to listen - and participate - is crucial. Employees must understand the importance of compliance (for them personally as well as for the business), what is and is not permitted, and when to seek help. This can be achieved best when employees feel invested in compliance rather than dictated to. To this end training and guidance should:

- Be tailored to the business area in question and deal with day to day issues and scenarios faced by the individuals involved. Enforcement action in the sector should be highlighted where possible, to demonstrate that the risks are real. For instance, provide 'real life' examples of emails or instant messages seized by the regulator to underline that their communications may be next.

- Be stimulating and interactive - individuals should not simply be asked to read instructions or listen to a list of prohibitions, but to think about and debate real life dilemmas, particularly where the legal position is not black or white (for example in relation to information sharing or future price announcements). Face to face training should take place regularly, at least for high risk employees, combined with interactive online training modules. Neither should be too lengthy. External speakers whose experiences will resonate with the audience - for example those who have been caught up in an antitrust investigation in the industry or ex-enforcers - should be considered.

- Where possible take a holistic approach, with scenarios raising compliance issues in addition to competition law - e.g. anti-bribery and corruption - as they would in practice.

- Emphasise the commercial benefits of compliance (as well as the risks of getting it wrong), such as the value customers place on integrity, and the potential to use competition law to challenge restrictive behaviour on the part of competitors or suppliers. Compliance should not be seen as a road-block, and therefore the emphasis should be on achieving commercial objectives whilst respecting the rules.

- Involve regular evaluation (with follow-up where necessary), including as an appraisal agenda point.

- Highlight mechanisms by which advice can be sought and concerns raised.

Above all, management must be genuinely and demonstrably involved, encouraging engagement through their public commitment to compliance. A video message from the CEO could be included in all training, for example. Management must also be kept engaged – for example by highlighting issues spotted and avoided, and general developments in the enforcement landscape.

- Maximise resources

Inevitable resource limitations must be managed effectively to best maximise compliance.

At the outset a risk assessment should be carried out to identify high risk business areas, teams, and jurisdictions, to be prioritised for training, and, if necessary, audit. This will enable face-to-face training (including one-on-one individual discussions where necessary) and specific guidance to be targeted where it is most needed. Online and other less resource intensive training methods can then be utilised for lower risk areas.

Legal resources will inevitably be stretched thinly, and therefore other functions should be involved in implementing the compliance programme where appropriate, for example HR in the identification of new starters and the arrangement of training sessions, general compliance/risk functions in the spotting of potential issues and filtering queries, and internal audit in any investigations. "Compliance champions" can also be utilised, not to resolve technical queries, but to highlight the importance of compliance and keep this on the agenda.

A holistic or "joined up" compliance approach which covers a variety of compliance issues can lead to synergies and therefore savings in terms of training and processes.

Finally, competition law issues should form part of the normal procedures for business planning and decision making, as with any other risks, enabling their routine consideration.

- Ensure "living" compliance

It is not enough to design a compliance regime and then leave it to gather dust. It must be kept under review and evolve to reflect external and internal changes.

There should therefore be a process for regular review and revision of the programme, for example to revisit initial risk assessments and update guidance and training to:

- Reflect new risk areas (both legal and factual).

- Include new examples and scenarios to reflect changes in business practice and reoccurring queries.

- Incorporate learnings from internal investigations/audits, and where applicable external investigations or complaints.

Feedback should be sought from the individuals who are subject to the compliance programme – for example as to the clarity of guidance and the quality or otherwise of training – and taken account of in revisions.

For business units and managers, a regular (say, annual) sign-off policy should require certification as to their knowledge of the programme and policy, the steps they have taken to implement it, identification of issues and improvements, and their confirmation that there are no problems of which they are aware. These can be tested via various mechanisms, such as spot-checks and audits.

Overall, the challenge is to ensure that any compliance programme does not exist in a vacuum. Rather it needs to form part of the company's culture, woven into education, training and corporate policy and governance. Simply having a compliance programme is not enough; it must be actively implemented, evaluated and updated, with deadlines for improvements set and met.