What We Can All Learn from US Military Innovation

I recently had the privilege of giving a presentation to the US Navy. To prepare for this speech, I spent time reading up on the history of US military innovation. Much of what I learned strikes me as equally useful to corporates. So I’d like to share a few of my observations.

American Innovation Wins Wars

As Americans, we are used to having the most powerful military in the world. We just assume we will have the fastest airplanes, the most ships, and the largest stockpile of the most lethal bombs. This overwhelming force can deter conflicts, because who wants to face that kind of firepower? While expensive, I am all for this strategy, because as they say, “the best war is the one we never have to fight.” Not to mention. I have a teenage son I’d rather not ship off to war.

But going back 200 years since our founding, I saw over and over, that the outcome of our conflicts has often hinged on American innovation.

Not Just High-Tech Innovation

Washington crossed the Delaware River at night during a mini Ice Age to surprise the British in Trenton. Most of his men couldn’t even swim. Henry Knox hauled 60-ton cannons captured in Ticonderoga to Boston. Dragged up onto Dorchester Heights in the middle of the night, these cannons so intimidated the British, they retreated to Halifax. These and many other examples showed me that over and over again, American forces win by doing the unexpected and seemingly impossible. Among a long string of such examples, it became clear that only a small part of our success has come from high-tech innovations.

One could argue that in WWII, the Germans actually had better planes and tanks than ours. Sure, the atom bomb was a decisive technical innovation, but not one you can use repeatedly or all life on Earth would end. In other cases, the US military relied on medical, tactical and low-tech innovations. Once we had contact with the enemy, we were able to develop innovations and then produce them at a scale the world had never seen

Other decisive US military innovations included:

Medical Innovations – During the American Revolution, General Washington defied the Continental Congress and vaccinated all 40,000 US troops against small pox. The technique, called “variolation” was against the law at the time. It involved making a small slit in the soldier’s arm, and squeezing some pus from a live smallpox pustule into the incision. The soldier would fall a little ill for a few days, then be inoculated against small pox for life. This innovation allowed the Continental Army to survive and develop into an effective and reliable fighting force, unhampered by recurring epidemics of that disease.

General Washington defied Congress to inoculate 40,000 troops against smallpox

Tactical Innovations — During WWII, some 1,100 creative Americans were recruited to a top-secret assignment as part of the US “Ghost Army.” This secret force was armed with truckloads of inflatable tanks, rubber guns and a massive collection of sound-effect records. They created the illusion of troop strength on European battlefields, to trick the Germans into deploying their forces in the wrong places. They are credited with saving some 30,000 lives.

The US Ghost Army hoists an inflatable tank

Low-tech Innovations — We recently celebrated the 75th anniversary of D-Day, and as you know, so many military technologies were spurred in WWII. But one of my favorites for its pure MacGyver quality was The Hedgerow Shredder.

Leading up to D-Day, no effort was spared in planning to get our forces across the Atlantic and onto the beaches of Normandy. But to our surprise, after landing, the forces were held back by hedgerows that ran across the Normandy countryside. Our tanks would try to ride over them, only to expose the tanks’ vulnerable underbelly for the Nazis to better shoot at.

Then a humble Sergeant Curtis G. Culin, a cab driver from Chicago, designed and built a hedgerow cutting device made from pieces of steel rail that the Nazis had strewn across the beaches to slow down an amphibious attack. When tested, the new device easily sliced through the hedgerows.

Within two weeks, sixty percent of the First Army’s Sherman tanks were modified into Rhinos. With the Rhinos, the First Army were able to proceed through the hedgerow country and crush the Nazi Army. This was scrappy American innovation delivered rapidly through high-speed procurement and production.

The Hedgerow Shredder was Macgyvered together by a Chicago cab driver

Innovate Like Its Wartime

A lot of ink has been spilled studying how the military innovates in wartime vs peacetime. Obviously in wartime, the urgency is there for Congress to act faster, to greenlight novel solutions. But with the technical complexity of our weapons, aircraft and ships today, most new systems take 8 to 10 years to be designed, built and delivered. This is fine in peacetime, but not if war breaks out. Or if we have to fight an entirely different kind of war than the last ones.

It can be argued that for the last 20 years of conflicts in the Middle East, the US has innovated more at a peacetime pace, despite being technically “at war.” The kind of conflict we have been fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan is referred to as “Low Intensity Conflicts” or LICs. I am quite sure I would not describe them as “low intensity” if I was dropped into one of these fights, But the scale, the style of fighting in a dense urban environment, is more localized than what we faced in WWII.

From my research, it seems that over the last twenty years, most of our military innovations have been incremental. Better night vision goggles, better load-bearing vests. This reflects our peacetime innovation mentality. It reflects wars we didn’t want to admit were dragging on, without a clear victory in sight.

To be ready for a very different kind of conflict, we need to innovate like it’s wartime.

Lethality…Is it the old way of winning wars?

I also noticed that since Vietnam, most of our innovation focus has been on killing more of the enemy faster….what the military calls lethality. But is this the way to win, when victory requires the other side adopting a different political outcome or system of government?

In the Vietnam war, casualty rates were extremely lopsided in America's favor. Yet, by 1976, South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were communist. The United States won almost all of its battles against the Viet Cong, but the communists still won the war. Clearly there is more going on in war than lethality and troop movements.

Despite the sacrifice and heroism of our men and women in uniform who have contained ISIS, the middle east wars are lingering nearly 20 years now. In the middle east, anger toward the US has never been stronger, and has fueled the rise of ISIS, a non-state actor. ISIS has not been extinguished and terrorism has spread to more countries, and even to our own shores.

They say the next US war will be against a near-peer such as China or Russia. Or perhaps against a burgeoning nuclear rogue nation like Iran or North Korea. America is preparing for these more conventional scenarios. That worries me. Because I see our foes shifting to the philosophy that “the best war is one you don’t have to fight at all,” using financial leverage, political, media, social influence, cyber and terrorism. Makes sense when the combatants are all nuclear players. We can’t afford to rely mainly on sheer lethality anymore.

The next war may never have a formal declaration. Just in May this year, Mitch McConnell got the Senate to drop sanctions on Oleg Darapaska when Oleg promised to invest $200M in an aluminum plant in McConnell’s home state, Kentucky. No war. No blood loss. Why declare war when victory is so cheap?

The parallel with corporates is that we often try to beat the competition by out-engineering our products. But maybe the consumer just wants a simpler product, or a simpler buying process. I worked on a P&G innovation addressing the developing world that was purposefully low tech. It was for women who rejected P&G’s premium-priced, highly engineered femcare products. Instead, it used an herb that women universally relied upon to soothe skin irritation. It became a $1 billion brand.

So what lessons can we take from the military for large corporate innovation programs?

- High-tech innovations, like block chain and AI, sound sexy. But you need to be prepared with a balanced portfolio of process innovations, product innovations, business-model innovations, marketing innovations and technical innovations.

- We need to innovate like it’s wartime. Because corporate executives get a paycheck regardless, it’s all too easy to defer a meeting or a decision. But you need to impose wartime conditions on your innovation decision-making. Assume your enemy is at the gate.

- Big ticket innovations get the CEO’s attention. But don’t overlook frugal innovations like the Hedgerow Shredder. Implement these quick wins fast.

- Remove the legal and procurement barriers to innovation, now. It’s easier to defy Congress when you’re General Washington. But you need to find out the myriad ways that your procurement, legal and security processes – designed for the maintenance of your existing business – get in the way of innovation at speed.

Today, most companies’ innovation efforts are incremental. These efforts have low yet reliable ROI in the single digits, whereas Disruptive innovation has an ROI around 70 percent. American organizations — both military and for-profit corporates — need to spend more time thinking about the kinds of “forces” and the kinds of “conflicts” we might encounter next, and disrupt ourselves before we are disrupted. Our military and for-profit corporates need to make sure we don’t fall into the trap of peacetime innovation thinking.

The US was able to recruit those 1100 Ghost army by targeting architects, performers and acoustic engineers. But do you know who your innovators are? Do you have enough of them? Are they deployed to imagine your disruptors and develop solutions to disrupt yourself? Are they aimed at your most pernicious problems?

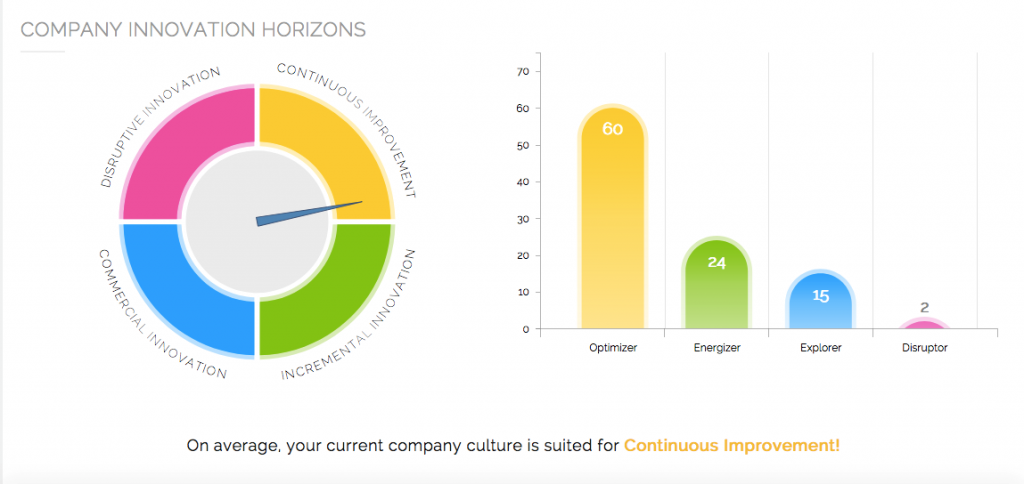

Someone recruited to “salute and obey orders” is not going to thrive in this environment. To stay even, you need a balance of talents across the four (not three) horizons:

- Continuous Improvement ~ 40 percent

- Incremental Innovation ~ 30 percent

- Adjacent Innovation ~ 20 percent

- Disruptive Innovation ~ 10 percent

If you are already facing the enemy, you need a workforce comprised of about 25 percent of each.

In most large companies the workforce is suited for Continuous Improvement

About the Author: Suzan Briganti is CEO and Founder of Swarm Vision. Swarm Vision is a software-as-service platform to identify, organize, develop and leverage innovation talent in the enterprise to drive growth. Suzan brings 25 years of experience in research, strategy and innovation. She has grown Swarm Vision from a garage start-up to a trusted solution provider to global Fortune 500 clients. Suzan leads Swarm Vision with a focus on building great products and teams. Suzan has an MBA summa cum laude from Boston University and a design degree from Italy. She serves on the International Standards Organization for Innovation Management (ISO 56000), representing the United States. Suzan is a frequent writer and speaker on innovation in the workplace. Contact: suzan@swarmvision.com