Earlier this month we asked our global subscriber base of LNG professionals to weigh in on some of the industry’s major talking points. Our questions covered everything from LNG bunkering to the emergence of new trading hubs, project financing, rising LNG shipping prices, and the impact of the trade war between China and the United States.

You can find the results summarised in the following report. They reveal the spectrum of opinion among LNG professionals on the big issues shaping the industry, as well their perceptions of the main challenges and opportunities for the years ahead.

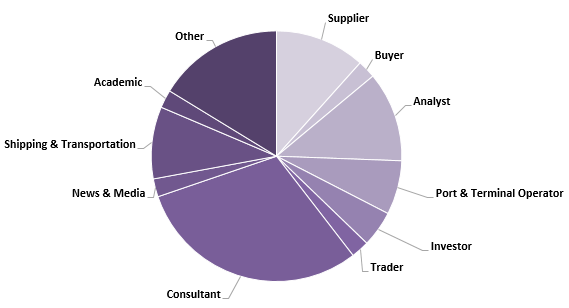

If you’re curious about who our respondents were, the chart below shows a breakdown of the survey-takers.

We also contacted a range of experts for a more detailed perspective on selected topics, including speakers from the LNGgc conference series and prominent academics. Read on for a summary of the context behind each question and our analysis of the results, plus insights from:

- Howards Rogers, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

- Carmen Lopez-Contreras, Repsol

- Susan Sakmar, University of Houston Law Centre

- Sean Strawbridge, Port of Corpus Christi

- David Ledesma, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

- Alain Bourgeois, Glowake

- Magnus Koren, Höegh LNG

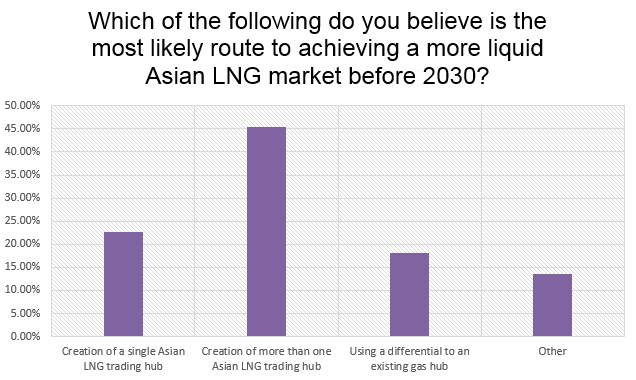

Which of the following do you believe is the most likely route to achieving a more liquid Asian LNG market before 2030?

Background in Brief: Developing greater liquidity has long been regarded as a key objective for the Asian LNG market. In North West Europe, which benefits from a higher churn rate and well-developed LNG trading hubs, prices tend to be lower and more consistent. More liquid markets are also able to respond to sudden spikes in demand with greater rapidity.

Improving liquidity in Asia is seen as a positive by both buyers and suppliers, as it should in theory help to grow LNG’s share against competing energy sources. Thus a range of options have been mooted for helping to increase pricing transparency – most notably the establishment of one or more Asian LNG trading hubs.

Breakdown: Almost 68% of survey respondents believe that at least one Asian LNG trading hub is in prospect within the next 12 years, with the majority of that number favouring more than one location. The probable whereabouts of a trading hub are covered in greater depth later in this report.

18% of respondents also felt that a differential to an existing gas hub – a more easily achievable short-term measure – would be the most likely outcome before 2030. Adopting this approach will certainly prove easier if it is accompanied by the growth of a trusted digital trading platform for LNG in Asia.

There were a number of alternative options proposed by survey respondents too. Some argued that the increasing proportion of US LNG cargoes (which tend to be shipped on destination flexible supply agreements, allowing the gas to be resold and re-exported) would itself prove a fundamental driver of liquidity. Others pointed to the growing role of commodity trading houses as a causal factor, and the construction of onshore receiving facilities and underground storage as a prerequisite for an increase in trading activity.

A common theme was that having more players involved, as well as greater overall demand, would help to stimulate the transition to a more liquid market.

Howard Rogers, Chairman of the Natural Gas Research Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, believes that the build in liquidity in the JKM forward curve is the thing to watch. “JKM seems to have emerged as the key trading benchmark, and as curve liquidity grows I would see this as the obvious reference for spot, short term and in time medium term sales agreements,” he writes.

“Shanghai and Japanese hubs (downstream of regas facilities and based on parcels of traded gas) - are the 'theoretically optimal' solution in terms of a reference - but even with government commitment to face down vested interests these will take at least 10 years to develop, based on UK and continental European experience.”

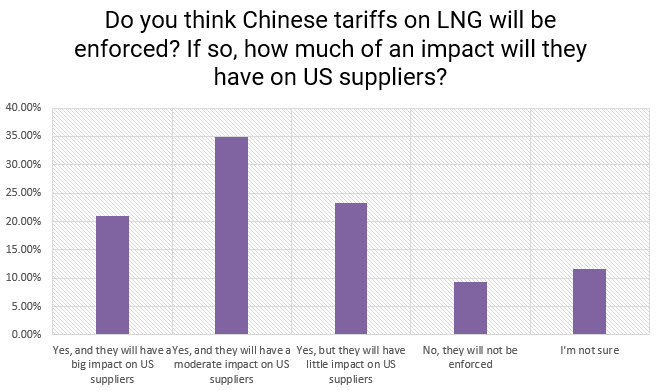

Do you think Chinese tariffs on LNG will be enforced? If so, how much of an impact will they have on US suppliers?

Background in Brief: On September 24th, China imposed a tariff of 10% on US LNG imports, a step down from an earlier threat of 25%. The tariff rate will rise to this level on January 1st, leaving the door open in the remaining months for a reassessment by either party as the effects of wider tit-for-tat tariff regimes become apparent.

LNG was left out of the original list of commodities targeted in July, which was interpreted variously as reluctance on the part of China to limit a promising source of natural gas supply, and as a tactical move intended to leave a bargaining chip still in play. Tariffs have so far yet to be announced on US crude.

Breakdown: The spread of opinion on how the trade war will impact US LNG exporters – both in the survey results and in media commentary on the subject – is pretty mixed. Alarmists say that it is imperative for US exporters to remain cost competitive in what will soon be the world’s largest LNG market, and that a 25% tariff would make this impossible. The CEO of LNG Canada, Andy Calitz, who fits squarely into this camp, recently opined that Chinese tariffs could leave many US LNG projects in the pipeline “dead in the water”.

Less concerned observers point out that the percentage of US LNG imported by China was at any rate never that large (China accounted for only 15% of US LNG exports in 2017). They further remonstrate that demand for LNG is growing so rapidly elsewhere that exporting to China may not be necessary. The flexible nature of the LNG market should also allow for other players, such as Japan and Europe, to purchase US LNG and resell it to Chinese consumers, in which case the source country will no longer be an obstacle.

Nonetheless, it is hard not to be troubled by the idea that we may be moving into a world in which the world’s largest producer of LNG (as the US is expected to become within the next decade) finds it very difficult to sell directly the world’s largest consumer (as China is expected to become within the next two years).

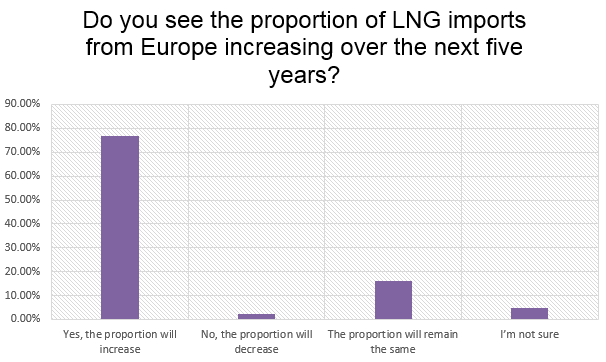

Do you see the proportion of LNG imports from Europe increasing over the next five years?

Background in Brief: How much LNG finds its way to Europe over the next five years will be influenced chiefly by two factors. One is the willingness of European nations and utilities to bear the higher cost of LNG imports compared to pipeline gas for reasons to do with security, supply diversification and seasonal flexibility. The other is the rate of demand growth in Asia, and how that affects the price spread between the two major consuming regions.

European LNG imports have been trending upwards over the last four years, but remain substantially below the volumes seen during the peak period of 2009-2011.

Breakdown: The feeling among survey respondents is strongly in favour of a rise in European LNG imports. Sean Strawbridge, CEO of the Port of Corpus Christi, casts the question as a contest between US LNG and Russian gas. He writes that we can expect more LNG imports from “NATO countries as US LNG has more attractive price stability, abundance, and a lower environmental footprint”. This will almost certainly be true of the Baltic region, in which the growth in pipeline gas consumption has historically been slowed by concerns about reliance upon Russia.

Poland’s Swinoujscie regas terminal has an average utilisation rate of 60%, making it the most heavily utilised LNG terminal in Europe. The terminal is scheduled for a capacity expansion from 5 billion cbm to 7.5 billion bcm, expected to reach completion by the end of 2022. Meanwhile, the Klaipėda LNG FSRU, which acts as Lithuania’s LNG terminal, is responsible for providing more than half of the country’s natural gas supplies as well as providing gas to Latvian and Estonian consumers. Lithuania has committed to retaining the terminal beyond 2024 to ensure that their supply portfolio remains diversified.

The other side of the question – the spread in European and Asian LNG prices – is perhaps a little harder to anticipate. Expectations of price convergence between the two markets have in the past been stoked by predictions of LNG oversupply. With the growth in Chinese demand, however, it seems more likely that the market is moving towards a state of supply shortage. That could pull more cargoes towards Asian countries with fewer alternative natural gas supply options, but perhaps not within the next five years, and only if new capacity additions fall short.

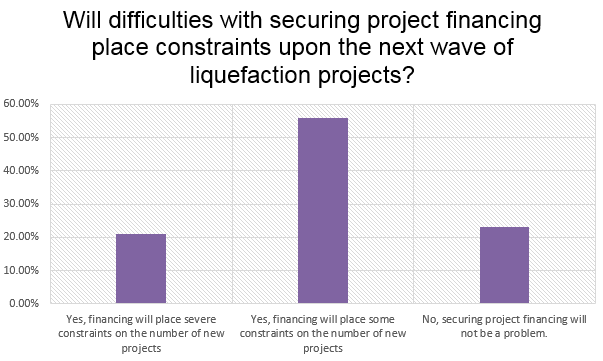

Will difficulties with securing project financing place constraints upon the next wave of liquefaction projects?

Background in Brief: Historically LNG export projects have been underpinned by long-term supply agreements, providing financiers with the assurance of a return on investment. As the duration of the average LNG supply contract has fallen, however, it has become harder for project developers to provide this level of certainty to potential investors. Some members of the industry have voiced concerns that this will make new projects harder to get off the ground.

Breakdown: The results of the survey suggest that there is still a genuine sense of concern about the way new projects can be financed, but that these worries are far from crippling. Carmen Lopez-Contreras, a Senior Market Analyst from Repsol, observes that “there are quite big players in the market with enough financial muscle to proceed with project FIDs. LNG Canada is an example, Qatar can go either for new megatrains or Golden Pass with no financing, BP at Tortue, and even Novatek and partners with Arctic LNG2.”

Susan Sakmar, an LNG expert from the University of Houston Law Centre, agrees that there is no shortage of money available for the right kinds of projects. “There is plenty of money sitting on the sidelines,” she writes, “and there will be project financing available for LNG projects with the right business model.”

“The real issue is whether there are enough credit-worthy buyers willing to sign long-term contracts. At the moment, the projects moving forward are those with large project sponsors that can finance on balance sheet and/or attract credit-worthy buyers, such as the Qatar expansion and more recently LNG Canada. The projects that are struggling to attract LT credit-worthy buyers will have challenges securing traditional LNG project financing. This doesn't mean that there won't be a next wave of liquefaction projects - there's already a new wave looming – it just happens to favour the major LNG players.”

Sakmar’s analysis supports the view that if smaller players are going to see new projects through to FID, they will likely have to take innovative approaches to sharing the cost of development and convincing investors of the long-term profitability of new projects.

On the other hand, David Ledesma, a Senior Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, has undertaken some research which potentially presents the situation in a more positive light. “At the OIES we have done some analysis that shows the potential third party financing requirements for new LNG liquefaction capacity over the next 5 years approximately equates to the annual average third party finance raised over the past 10 years,” he writes.

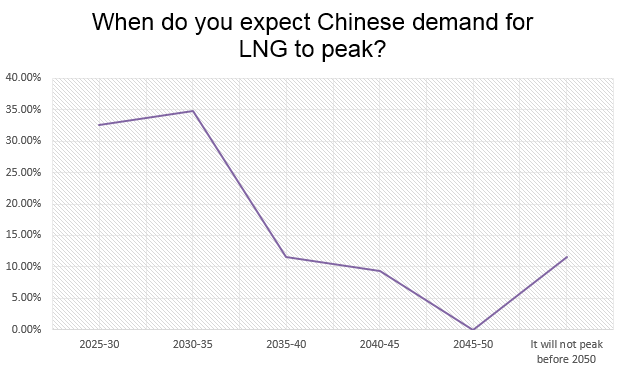

When do you expect Chinese demand for LNG to peak?

Background in Brief: 2017 saw a massive surge in Chinese LNG demand as the nation moved away from coal as part of its effort to fight air pollution. In total, natural gas consumption rose by 15% year-on-year and LNG imports by 46% year-on-year. LNG demand this year is expected to rise by another 12 million tonnes according to a recent Wood Mackenzie report.

Swift growth will be sustained over the coming years, but may be dampened by new infrastructure projects such as the Power-of-Siberia pipeline from Russia (expected to become operational in 2019), and the construction of additional storage capacity, allowing China to import more pipeline gas year round. Long term, the timeline for a peak in LNG demand is likely to be determined by the rapidity with which China can shift to renewables.

Breakdown: The survey results indicate that the majority opinion is that China’s demand for LNG will peak some time shortly before or after the year 2030. Sean Strawbridge writes that demand is unlikely to plateau “for at least another decade as the People’s Republic of China reduces its environmental impacts by converting to LNG from solid fuels such as coal. The Trump Administration also wants to see more exports to China in an effort to reduce the current $375 billion trade deficit.”

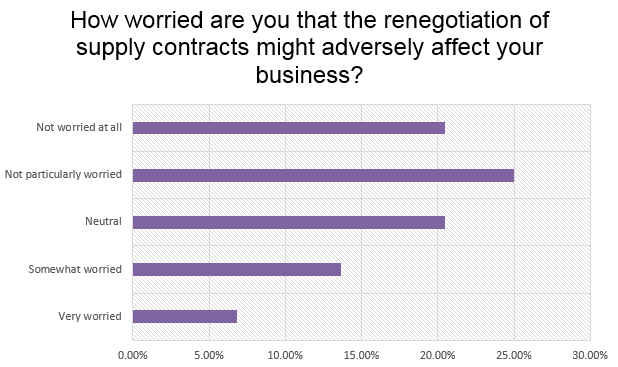

How worried are you that the renegotiation of supply contracts might adversely affect your business?

Background in Brief: Hastened by the involvement of portfolio players and trading houses, a growing number of LNG buyers are seeking to replace rigid, destination restricted long term supply agreements with a more flexible mix of contract durations and clauses. As agreements come to an end, they are naturally being replaced by contracts which better reflect the current state of the LNG market, often with pricing arrangements indexed to hub prices rather than the price of oil.

However, some exporters have expressed concerns that buyers may seek to renegotiate contracts before they expire.

Breakdown: Only 20% of respondents admit to being worried that contract renegotiation might adversely affect their business. This can perhaps best be explained by a majority view that contracts will need to change to accommodate the changing needs of buyers.

Susan Sakmar writes that contract renegotiation should be seen in the context of an evolving industry: “there’s no doubt the LNG industry is evolving to a more commoditized market and LNG contracts are already reflecting the shift to a more liquid, dynamic market. For example, as LNG comes off contract, there is a definite shift away from destination restriction clauses - especially in Asian contracts. These type of clauses will eventually be a thing of the past, but that shouldn't have an adverse impact on the LNG industry. Both buyers and sellers recognize the industry has changed so contract terms need to be more flexible.”

David Ledesma agrees that contract renegotiation should not pose too much a worry, but is careful to distinguish between contracts that are ongoing, and those that are expiring: “If you are talking about the renegotiation of SPAs that are expiring (I.e. contract extensions) then I don’t see this as a problem. These contracts have run their course and any new terms will reflect the realities of today’s market. If you are talking about buyers or sellers breaking open non-expired contracts, then I have more concerns as that would upset the status quo of the existing market.”

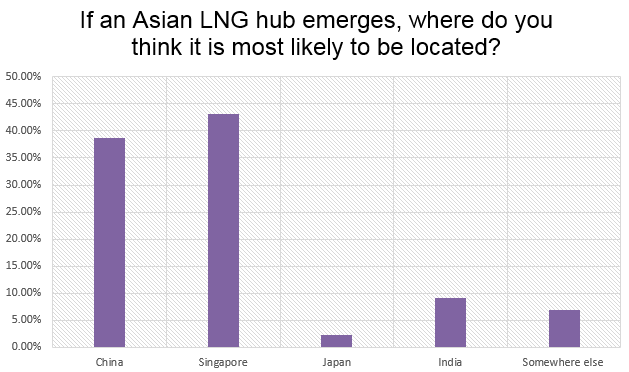

If an Asian LNG hub emerges, where do you think it is most likely to be located?

Background in Brief: As covered by the background summary to question four, establishing an LNG trading hub in Asia – in the mould of natural gas trading hubs like TTF and NBP in Europe, or Henry Hub in the US – has long been viewed as a needed step towards creating a larger, more liquid Asian LNG market. The creation of at least one LNG trading hub in Asia within the next 12 years is also seen as probable by over 68% of survey respondents.

For Asian buyers, a domestic hub would help to create a pricing reference which better reflects the level of demand in the region. Although a number of commonly used pricing benchmarks are available for LNG in Asia, such as Platts JKM, they essentially act as stand-ins for a more reliable hub price. Existing benchmarks rely on the voluntary reporting of prices by market participants, and are therefore less accurate than a transparent hub price based on a high volume of trades.

Japan, China, Singapore and India are all currently vying to be the first to develop an Asian LNG trading hub.

Breakdown: The results are split fairly evenly between China and Singapore as the favourite, with the latter gaining a slight edge. Somewhat surprisingly, given that it was the original import market for LNG and still the world’s largest customer, only 2% of attendees felt that Japan would be successful in its bid to build an LNG trading hub. By contrast, India – something of a dark horse in the contest – gained a respectable 9%.

There are a number of reasons why Singapore may have emerged as the favourite. For one, befitting a major financial centre it is has an active community of traders and 45 LNG trading desks. The Singapore Strait is also the busiest shipping lane in the world, meaning that the region will play a key role in the development of LNG as a marine fuel. Another tick in the plus column is that the city state boasts a liberal regulatory framework favourable to the development of a hub. On the other hand, it is a much smaller market than each of the alternatives, and may encounter problems interesting a sufficient number of participants.

China is also a promising candidate. The country already has a relatively diverse range of supply options compared to the alternatives – including domestic production, pipeline gas and LNG imports – which should help to support the trading volumes needed to establish a hub. The Chinese state is also pushing for better price discovery through the creation of trading exchanges like the Shanghai Petroleum & Natural Gas Exchange and the Chongqing Oil & Gas Exchange, although participation is at present still modest. Negatives for a Chinese LNG hub are heavy state involvement both in the regulation of prices and in upstream and midstream development – but deregulation is on the agenda.

As to Japan, the country benefits from a market that is large and well-developed, with deregulation having been initiated as early as the mid-1990’s. Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has set the target of achieving LNG hub status for the country by the early 2020’s. However, progress in Japan so far has been slow, and the future is uncertain. A lack of gas supply alternatives makes the status of a hypothetical Japanese LNG trading hub conditional upon a well-supplied market. If undersupply kicks in around the mid-2020’s, there are some doubts that a Japanese hub could perform the function of re-exporting cargoes which would also be needed to meet its own domestic demand.

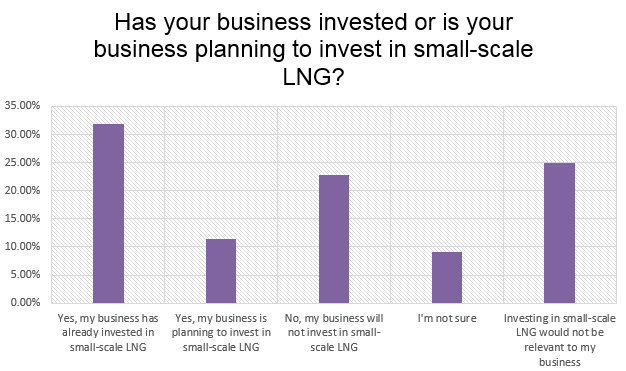

Has your business invested or is your business planning to invest in small-scale LNG?

Background in Brief: The use of LNG in its liquid form, without the need for regasification, has come to be seen as one of the most promising growth regions in the natural gas industry. This is because small-scale LNG allows gas to play a role in places it previously couldn’t: generating power in regions without well-developed pipeline infrastructure, and acting as a fuel for heavy haulage and shipping.

Engie expects the small-scale LNG market to expand to 100 million tonnes of annual demand by the year 2030. Marine bunkering alone is expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 62.5% according to market research group Energias.

Breakdown: Discounting respondents for whose businesses an investment in small-scale LNG would not be relevant, over half the survey-takers said that their businesses either already has or will invest in small-scale LNG at some time in the future.

Alain Bourgeois, Managing Director of advisory firm Glowake, is similarly up-beat about small-scale, writing that “small-scale LNG – in all its forms (smaller carriers, milk-run delivery, trucking, bunkering...) – will be a significant instrument to grow the market in the coming years. Both in emerging economies lacking pipeline infrastructure and to address new niche segment markets.”

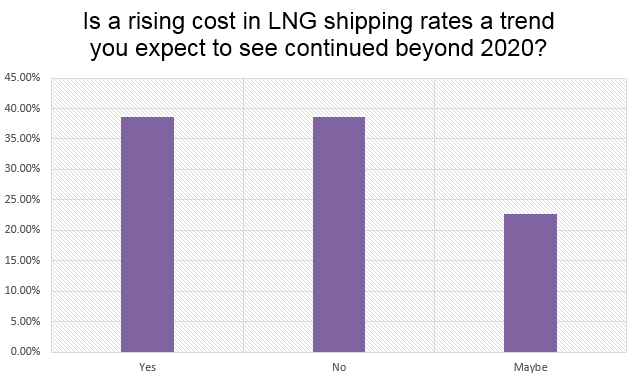

Is a rising cost in LNG shipping rates a trend you expect to see continued beyond 2020?

Background in Brief: The last twelve months have witnessed a steep climb in LNG shipping rates. Where the cost of chartering a vessel to carry a cargo of US LNG to Asia averaged between $30,000 and $40,000 per day last year, that cost had risen to $95,000 by September. In the last few weeks, rates have risen closer to $140,000. LNG shipping firms are confident that high prices will be sustained at least through to 2019.

The problem for exporters is that growth in the fleet of LNG carriers is not keeping pace with new liquefaction capacity additions. Prices over the last year have been further exacerbated by a rise in bunkering costs, and an increase in Panama Canal tolls rates. Shippers have taken to chartering vessels for longer durations to lock-in prices ahead of further rises.

The IEA’s third Global Gas Security review, published last week, includes a warning that the “risk of a lack of timely investment in the LNG carrier fleet could pose a threat to market development and security of supply.”

Soaring prices are also having a significant impact on where cargoes are heading. With the costs of shipping US and Russian LNG cargoes to Asia often exceeding any potential gains from higher Asian spot prices, more LNG is finding its way to North-West Europe in the short-term.

Breakdown: Respondents are split right down the middle about when prices are likely to come down again. For both suppliers and buyers, higher shipping costs are not good news – if LNG is more expensive to transport, the range of potential suppliers is reduced, and the fuel loses competitiveness against alternative energy sources.

For the shipowners themselves, however, a short-term mismatch between capacity additions and shipping tonnage will be a boon. Magnus Koren, a Market Analyst for Höegh LNG, believes that the outlook for LNG shipping companies is bright. “The LNG market is strong, and the next couple of years look very promising given the impressive expansion of liquefaction capacities across the board. There is no doubt that huge new volumes of LNG are about to hit the market and this will obviously require a lot of tonnage, especially since the distances from exporters to the market in many cases are long,” Koren writes.

“Even as the global fleet of carriers is also growing fast, we share the belief that the shipping market will be tight in the near term. At the same time we’re a little more cautious when looking a further into the future. The question is what happens if the fleet keeps growing while the increase in liquefaction capacities flattens around 2021?”

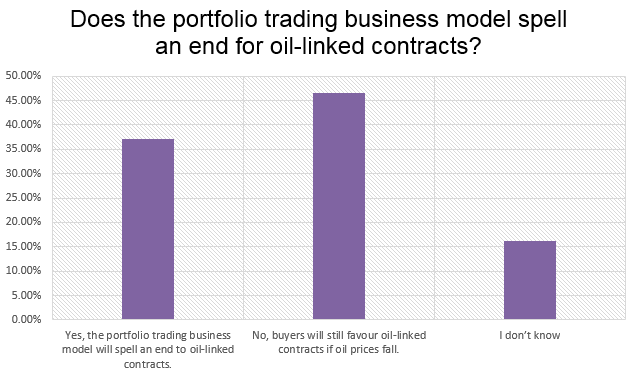

Does the portfolio trading business model spell an end for oil-linked contracts?

Background in Brief: A shift away from oil-linked contracts is one of the enduring motifs of the broader discussion around commoditisation, the decline of long term supply agreements, the increase of market liquidity and the development of LNG trading hubs.

It isn’t difficult to see why contractual prices being determined by a separate commodity is seen as a sub-optimal solution by many LNG buyers. As oil has over time become less likely to compete with gas in power generation, and substitutions are therefore more infrequent one way or the other, the logic for linking the two fuels has diminished. Likewise, there is little reason for reductions in oil demand, unforeseen geopolitical occurrences or temporary supply restrictions that have no bearing on the availability or desirability of gas spiking the prices customers pay for LNG.

Long term, oil-linked contracts were a consistent feature of the simple, point-to-point market structure that has historically characterised LNG trade. Some commentators have therefore interpreted the rise of so-called portfolio players in recent years as a sign that oil-indexation is on the way out.

Portfolio players are typically large oil & gas majors that subvert the point-to-point model by a.) purchasing stakes in both the upstream and downstream components of the LNG supply chain, and b.) retaining a diverse range of offtake agreements with varied contract durations.

Breakdown: Survey respondents were generally in favour of oil-linked contracts remaining – at least for the time being. Both David Ledesma and Carmen Lopez Contrerras are confident that there is a continued role for oil-indexation, casting it as one of an expanding range of options available to buyers. “The portfolio business model increases choices for buyers as their portfolio optimization allows them to bear risks like indexations risks,” Contrerras writes. Ledesma makes a similar point, arguing that the “pricing of LNG on an oil basis will just be one of the price indices used in trading LNG.”

Howard Rogers comes to a different conclusion.He is of the opinion that the portfolio trading business model will eventually bring an end to oil-linked contracts, but writes that “the number of projects needed for the mid-2020's is probably more than the Majors (who have LNG Portfolio businesses) can finance (without non-recourse loans from Energy banks). So I think there is still a place for the 'next wave' of LNG projects for oil-indexed LT contracts for some of the volumes (but not as high as in the past).”

“Key players such as China may agree to oil-indexed contracts to help float LNG projects deemed by them to be of strategic importance (such as Yamal and Arctic LNG in Russia and East Africa). For a while major portfolio players who were too slow to get into areas such as East Africa may underwrite the offtake with oil indexed contracts. Eventually (i.e. beyond the next wave) I think it will become ever clearer that oil indexation of LNG represents a huge cross-commodity risk - especially as renewables and coal really start to squeeze gas's market share in the late 2020's.”

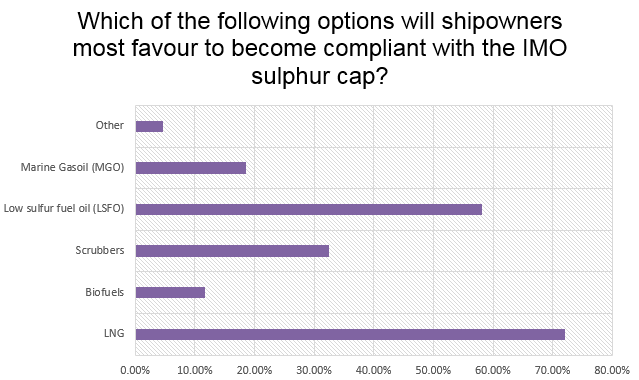

Which of the following options will shipowners most favour to become compliant with the IMO sulphur cap?

Background in Brief: The shipping industry is currently making a rapid transition to alternative fuel sources as a result of the IMO’s Sulphur 2020 regulations, which will limit the maximum sulphur content of bunkering fuel to 0.50% m/m. LNG has emerged as one of the leading options given its emission reductions profile: 100% fewer sulphur oxide and particulate matter emissions, and 90% fewer nitrogen oxide emissions. Alongside alternative fuel sources, a certain percentage of the global fleet will also adopt scrubbers, a technology designed to remove SOX directly from exhaust gasses.

Breakdown: Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the vocation of the survey respondents, LNG emerges as the clear winner. The survey allowed for the selection of more than one option however, so it is probable that was an agreed upon choice. The actual peak proportion of the global fleet anticipated to adopt LNG as a fuel is probably closer to 5% - a figure unlikely to be reached by 2020.

Alan Bourgeois is a good person to turn to place things in their proper context. He writes that a “fact check is that most ship-owners are going the compliant fuels (VLSFO, MGO…) route. Scrubbers get a lot of attention due to expected quick returns for ship-operators having retrofitted vessels on due time, due to expected short-lived high HS/LS spreads. Longer term, most investors see that open-loop will face regulatory challenges and closed-loop operational hurdles and unexpected costs.”

“LNG will attract more and more attention post 2020 for new-builds, along with bunker supply spreading globally. LNG is probably the best transition towards zero emission vessels. The future is with combination of solutions: LNG, biofuels, hybrid, fuel efficiency… and longer term green hydrogen or ammonia if available in required quantities for deep-seas shipping.”

The five year outlook

| The biggest challenges for the LNG industry over the next five years (according to survey respondents) | The biggest opportunities for the LNG industry over the next five years (according to survey respondents) |

| Reducing methane leakage in the value chain. | New importing countries |

| Finding a place for gas/LNG in the energy transition | Marine bunkering |

| Maintaining a market equilibrium of demand & supply | Gas-to-power for remote communities |

| Competing alternatives for small-scale applications | Shift from oil to gas |

| Resource nationalism | Arbitrage trading opportunities as a result of rising volatility |

| Reducing infrastructure cost and deployment time | Developing small (otherwise stranded) fields |

| Lack of sufficient "credit worthy" LNG buyers | Coal to gas conversion in Asia |

| Lack of experienced hands in recruitment pool | New entrants for small-scale LNG |

| Portfolio players pushing out smaller companies | LNG as a fuel for heavy haulage |

| Ensuring high prices do not destroy emerging market demand | Continued growth of floating solutions (FSRU and FLNG) |

| Increasing LNG storage infrastructure | Potential for nuclear failure in the far east |