Breaking Down Ethics: Imperatives and Conflicts

In my previous Insight, we looked at the importance of avoiding ‘amoral’ behavior by identifying, and neutralizing, the four enablers of self-deception that can hide ethical dilemmas from view. Of course, simply acknowledging the existence of an ethical dilemma, while a good start, does not in itself provide a solution. Ethical quandaries of any nature are often complex, messy and hard, and it is easy to feel unmoored and overwhelmed.

There are a number of models out there that can help frame ethical decisions, but one that I find particularly useful is Roger Steare’s ‘Ethicability’ presented in his book ‘Ethicability: (n) How to Decide What’s Right and Find the Courage to Do It’.

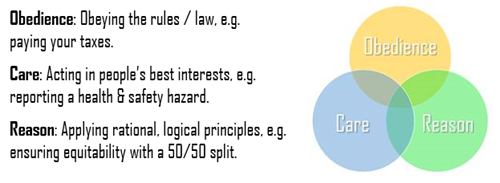

According to Steare, when faced with having to make an ethical judgement there are three ‘Ethical Imperatives’ that we must consider.

When presented with an ethical dilemma, it is therefore always worth asking yourself the following questions:

- Which processes/policies/laws must be followed? Which apply in this situation?

- What would a reasonable person consider to be your duties of care to yourself and others?

- Which course(s) of action would make most sense from an objective, neutral perspective, applying impersonal criteria and reasoning?

Often, more than one (in fact, all three) imperatives can be in play when faced with an ethical decision, and ideally they should be mutually reinforcing. However, sometimes it can feel like one or more imperatives may be in conflict. These are ‘external’ conflicts, and when they occur it is worth exploring what those conflicts might be, and how you can resolve them. Some good questions to ask would be:

- Which of the three imperatives are most important/relevant in this situation?Why? Who is the best person to judge this?

- In what respects are the imperatives mutually reinforcing in this situation? Where might they be in conflict with each other, and how could that be resolved?

- What would be the ideal outcome to this situation? What outcomes do you want to avoid? What is realistic/possible?

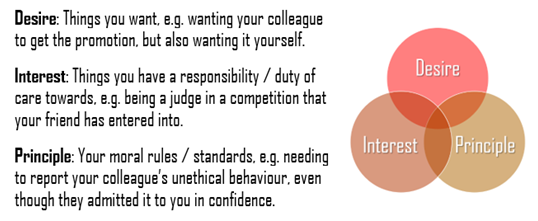

The above questions can help you to structure your thinking, and start to find a way through the ethical dilemma. However, sometimes it feels really hard to step back and take an objective view of the situation. When this is the case, we may find that we are caught up in one or more of the three ‘Ethical Conflicts’ that can complicate ethical judgements.

As with the Ethical Imperatives, often more than one will be in play in any given situation. These represent ‘internal’ conflicts within ourselves, and are the most challenging, so it is important to consider the possibly of whether one or more of these conflicts could be skewing your judgement.

If you find yourself feeling conflicted, ask yourself:

- Which of the three conflicts may be in play? Who would be the best person to judge this?

- Which is weighing on you most? In what ways might it cloud or skew your moral judgement?

- What steps can you take to avoid that happening?

Often, the best way to manage internal ethical conflicts is to apply the three ethical imperatives. For example, if you are a judge in a competition that your friend has entered into, there may be an ethical imperative of Obedience, in the form of a formal policy preventing you from judging entries that have been submitted by friends or family. You may consider that it is not in your friend’s best interest for you to judge their submission anyway (Care), as they themselves may feel uncomfortable, and if they won they may not feel they did so in a credible fashion. You may feel that it wouldn’t be fair from a consistency point of view (Reason) because several years ago you were in a similar position when a friend entered a competition where you were judge, and you recused yourself then. So why would you not this time?

Ultimately, when making decisions about what course of action you want to take, you need to make sure you listen to your “head”, i.e. what you think makes most rational sense, and to your “heart”, i.e. what feels right, and whether you feel comfortable with the decision. It is really important that both your head and your heart are equally satisfied with the final decision, as it will never be perfect, and things rarely work out exactly as we intend. The Ethicability framework is just that, a framework, and provides no answers, but I think it goes a long way towards helping us at least ask ourselves the right questions and keep ourselves honest.

Ethical dilemmas can cause a great deal of angst, and naturally we are fearful of making the wrong call. However, I firmly believe that from an ethical standpoint, the right or wrong call must not be judged on the outcome (which is where we so often focus our attention) but rather on the process that went into the decision. In a complex, imperfect world, the only thing you can hold on to at the end of the day is the fact that you made the best decision you could, in good faith, and in accordance with your values, based on the information that was available to you at the time.

In his essay Self-Reliance, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes “nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.” It is a notion that is at once cautionary and liberating.