Europe is stepping up its green ambitions

The present European Commission has high ambitions when it comes to climate and energy policy. It wants the European Union to set the worlds cleanest climate standards. By 2050, the EU should be climate neutral and fossil free.

At the same time, while in the member states, the EU targets for 2030 have widely not been implemented yet, and while key issues still have to be finalized at the Brussels level, the European refining sector comes out with its vision of a decarbonisation of the fuel sector.

Are these decarbonisation efforts going to be a good thing for the biofuels industry, or should the sector get worried?

Dreaming green

In December last year, the Commission published its Green Deal.* It sets out the EU's climate and energy ambition for 2030 and 2050 which has a broad agenda: new targets for 2030 and 2050, increasing circularity, adjusting agricultural policy, restoring biodiversity are integral part of this ambition. Dedicated funding needs to be put in place and the transition needs to be a social one 'leaving no one behind'.

In the annex to the Green Deal around 50 actions are listed mainly strategy documents but also several revisions of existing as well as new legislation. The majority of the listed actions are on the role for this year. Just to name a few already issued: an EU Climate Law, a strategy on agriculture (Farm to Fork), industrial policy, biodiversity, energy system integration, hydrogen and an action plan on circular economy.

Next to those strategy papers, the Commission set up several public consultations on various policy issues and is consulting the public on so-called roadmaps (outline for revising policy or legislation). Many of those initiatives do have directly or indirectly implications for the EU biofuel industry.

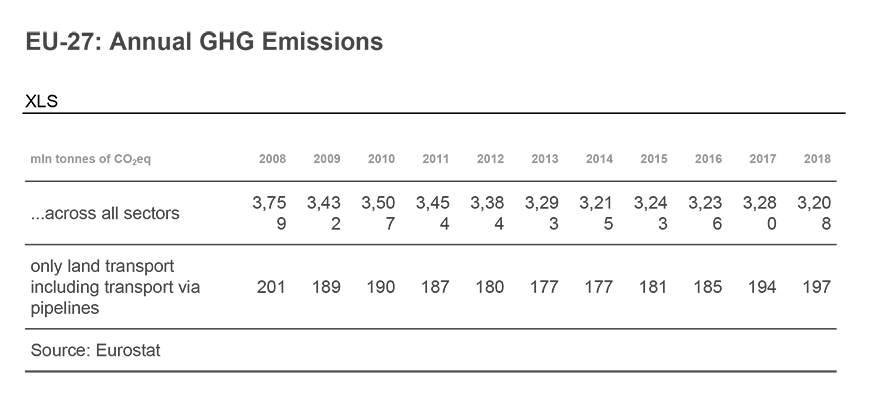

Medium-term, the biggest challenge to achieve the target of climate neutrality in 2050 is to increase the EU's greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions target for 2030 to at least 50% or 55% compared with 1990 levels (it is 40% now). From the discussions it becomes clear that the 40% will go up, likely to 55%.

Higher targets mean that much of the laws and regulations addressing emissions from the transport sector, still one of the big emitting sectors, need to be amended and highly likely on short notice (before 2023). Insiders expect;

- a revision of the Renewable Energy Directive II (RED II) earlier than foreseen,

- an adaptation of the Emission Trading System (ETS), possibly also expanding the number of sectors (transport is considered),

- a new Energy Taxation Directive,

- an update of the Directive on Alternative Fuel Infrastructure, mainly to create additional incentives for charging infrastructure and hydrogen uptake, and, very likely also

- an update of the standards on the emission of vehicles.

The latter is crucially important as it is seen as the best legal instrument to boost the uptake of electric vehicles and has undoubtedly ramifications for the uptake of liquid and gaseous biofuels.

The European Commission, especially the Directorate Generals dealing with climate and transport (DG Climate Action and DG Move) are usually seen as big supporters for electrifying transport as soon as possible. Internal combustion engines in passenger cars should be phased out entirely, and biofuels only at best in trucks, ships and aviation. Aviation is seen by DG Move being a sector where biofuel (and e-fuels) can play an important role. Earlier this year, the Commission organized a stakeholder event on decarbonizing the aviation sector and at the end of that meeting it became clear that the Commission submit legislation early next year to make the use of biofuels mandatory in this sector from, possibly from 2025 onwards.

Transposition and implementation of the RED II

During this upheaval of the EU energy and climate policy, it is still business as usual. Member states need to transpose the RED II by mid next year at the latest, even though a draft RED III could appear as soon as next year.

How far the various member states are in this process of transposition is unclear. That the sense of urgency is different per member state becomes clear if one realizes that Germany still needs to submit a draft law whereas the Netherlands have the draft law already finished and are putting together the national implementation rules.

Maybe some member states will not bother transposing the RED II at all, Brussels sources said. After all, what is the purpose of going through the complicated process of drafting national law and maybe a lengthy process of getting it adopted, knowing that the RED II may be changed dramatically or disappear altogether.

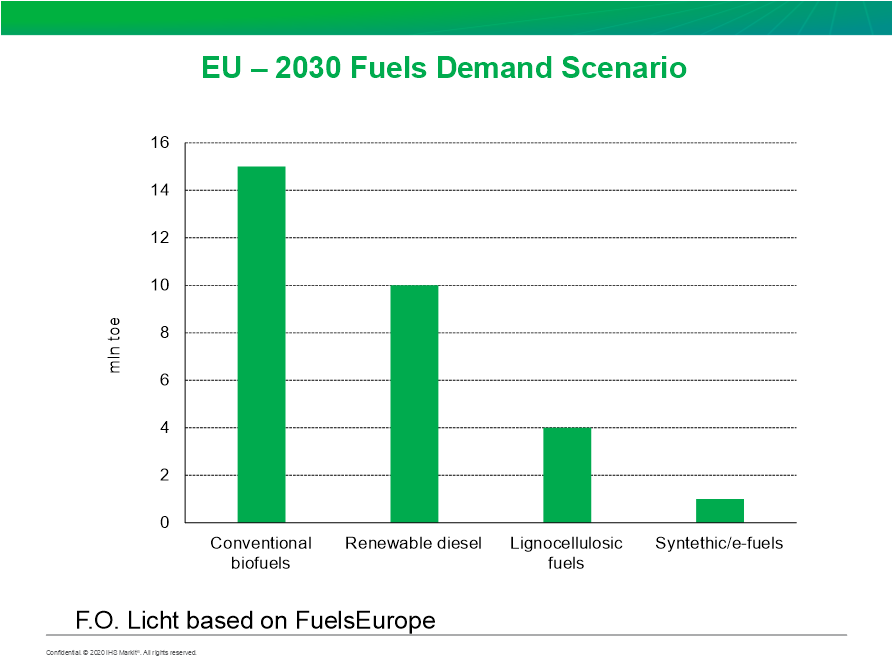

EU – 2030 Fuels Demand Scenario

An additional complicating element is the fact that the Commission is still working on RED II implementation rules (so-called Delegated and Implementing Acts) that do have an impact on understanding RED II and drafting national rules.

An additional complicating element is the fact that the Commission is still working on RED II implementation rules (so-called Delegated and Implementing Acts) that do have an impact on understanding RED II and drafting national rules.

About 16 of these Acts need to be drafted and adopted and to date, just one was published.** Crucially important ones like;

- establishing criteria for certification of low indirect land-use change-risk biofuels,

- designing a methodology on the use of biofuels in refineries,

- a methodology on assessing GHG emission savings from renewable liquid and gaseous transport fuels of non-biological origin and recycled carbon fuels,

- setting the appropriate minimum threshold for GHG emission savings of recycled carbon fuels, as well as

- amending the list of feedstocks in parts A and B of Annex IX in order to add feedstocks,

it is all still work in progress. Some of these acts will maybe get adopted this year but considering the complexity and sensitivity of these topics, delays are very likely.

For the biofuels industry, it becomes increasingly difficult to operate in a policy environment that is characterized by constant change, incomplete rules hence uncertainty.

Also, the earlier mentioned lack of synchronic and timely transposition of the RED II at national level adds to this uncertainty.

Not only the slow process of transposition and drafting implementation rules contribute to uncertainty also a lack of clarity on how to understand EU rules in force are cause for concern.

One example is the Fuel Quality Directive. It was always been assumed that the famous Article 7a, which requires fuel suppliers to reduce by the end of 2020 emissions of their fuel by 6% compared to 2011, was a sunset clause. In other words, after that year the 6% target would no longer be in force. However, the Slovak authorities were not certain that this was the case, industry sources reported, and asked the Commission for clarification. In a letter to the Slovak authorities, the Commission informed them that that member states should “ensure that fuel suppliers respect the 6% target after the year 2020”. Subsequently all member states were informed. One insider concluded that if member state authorities are not sure how to read and apply the law how could one expect industry to know?

Industry views: shifting gears

Amid all those announced changes in EU strategy, policy, legislation and the work at member state level to transpose and implement RED II the fuel, both fossil and bio, industry needs to reposition itself. What will the future hold and will the present business model still be fit for purpose in the next five to ten years?

It is not surprising that in the sector of transport fuels all stakeholders started issuing views on the 2030 and 2050 goals.

For the biofuel industry the reflections of the fossil fuel industry are crucially important. Does this industry, and the car industry for that matter, feel liquid and gaseous fuels will still be needed post 2030? And if so, what transport sectors are most in need of those fuels and in what volumes and, above all, what type of fuel?

FuelsEurope, the EU trade association of the big oil industry, issued its view on alternative fuel needed up to 2050.*** In their scenario up to 2030, crop-based biofuels will remain the largest source for alternative renewable fuel, followed by advanced biodiesel. The use of lignocellulosic, waste and residue-based biofuels will ramp-up gradually and mid the coming decade e-fuels (also known as renewable fuels of nonbiological origin) as well. Also, from 2025 onwards the use of green hydrogen in refineries combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS) will have positive effects on reducing emissions from fuels. Savings achieved by 2030 would be in the order of 30 mln tonnes of oil equivalent (toe) with an investment cost of up to EUR40 bln. The turning point is after 2030: no more crop-based biofuels and predominantly lignocellulosic, waste and residue-based biofuels as well as e-fuels. The share of advanced biodiesel remains fairly limited.

The objective is to have zero emission in road transport and minus 50% in aviation and maritime. Total investment needed to build the required production of these fuels is estimated at around EUR700 bln.

Whether this is a realistic scenario, no-one knows of course. But neither is the often-communicated scenario of full electrification of all transport in combination with green hydrogen (meaning even more renewable electricity needed).

It is therefore fair to assume that in the coming two to three decades, molecules will stay important alongside a growing market share of electrons.

However, the FuelsEurope scenario carries an important message: after 2030 for the refinery business seems to prefer to use only biofuels from waste, residue or dedicated energy crops. Knowing the weight of the refinery business in the economy, it is likely that the 'wishes' of the oil industry will be picked up and endorsed by regulators, the biofuel sector fears. For the crop-based parts of the sector, it means shifting gears within the next nine years.

If indeed this scenario of the oil industry will get traction amongst EU regulators the next RED will have much higher targets for advanced biofuels, introduce targets for e-fuels, possibly also for aviation and will further limit the use of crop-based biofuels as well as waste oils.

* Com(2019)640 final

** Commission Delegate Regulation 2019/807 regards the determination of high indirect land-use change-risk feedstock for which a significant expansion of the production area into land with high carbon stock is observed and the certification of low indirect land-use change-risk biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels. OJ L133, May 21, 2019.