Sugar glut may boost India's ethanol industry

After a stretch of very poor harvests the sugar industry in India may reap another bumper sugar crop in 2018/19 (Oct/Sep), after producing already more than 31 mln tonnes this year.

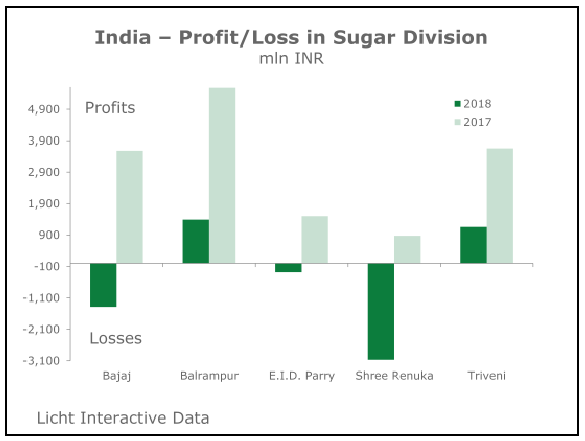

The ample supplies on the domestic market have pushed down sugar prices and this will show in the financial reports of the sector. After a return to profit in 2016/17 the sugar divisions of most companies will have moved back into the red again this year.

This negative trend is likely to continue in 2018/19 on expectations that the country will again produce more sugar than it needs for internal consumption. This constellation could spell disaster as low sugar prices will meet with high values for sugarcane. This will lead to a considerable margin squeeze and many millers will not be in the position to pay farmers for their cane.

Industry sources say that the total cane payment arrears could reach as much as INR250 bln (USD1=INR67.49) this year, the highest ever.

Want more articles like this? Sign up for the KNect365 Energy newsletter>>

As in the past, stake-holders have now turned to the central government in New Delhi to bail them out.

Good weather drags down sugar industry margins

Of course, the Indian government is no novice in the world of state interventions in the sugar market but the current and the prospective situation may still pose a special challenge. After all, the sector is drifting into one of its deepest crises ever as ideal weather conditions lifted sugar production in the two key growing regions of Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh to new record highs.

Before the start of the season the Indian Sugar Mills Association (ISMA) expected a crop of somewhat more than 25 mln tonnes, white value, up 25% on the year. However, in subsequent months the impact of the favourable weather in Maharashtra started to leave its mark on the projections. Now, as the season is almost over, 32.0 mln tonnes are expected to be produced. This compares with the previous record of 28.36 mln tonnes in 2006/07.

This means that benign weather has added 7 mln tonnes of sugar within a couple of months.

For 2018/19 no material change is on the cards. The monsoon in the cane growing areas was normal and so far there are no reports that farmers switch out of cane in droves. In essence this would mean that

• in Maharashtra the local industry could again produce over 10.5 mln tonnes.

• Uttar Pradesh would remain the biggest sugar producing state with over 11 mln tonnes.

• Karnataka, which like Maharashtra had suffered from drought conditions in 2016/17, could again produce around 3.6 mln tonnes.

Overall, the production of sugar could rise to 33 mln tonnes, white value. In view of the expected glut it is hardly surprising that ISMA is intensely lobbying for government assistance. In order to facilitate cane payments, it is asking Delhi to grant direct subsidies towards the cane price fixed by the government (the so-called FRP, Fair and Remunerative Price). While not specifying a number, ISMA said that this subsidy must be considerably higher than the INR45 per tonne that had been paid in 2015/16.

According to ISMA's calculation, the mills in the country can pay INR2,300 per tonne of cane. For the 2017/18 season, the federal government fixed the floor price at INR2,550, while Uttar Pradesh raised the rate to INR3,150. This leaves a gap of between INR250-INR850.

In May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's administration approved a subsidy of INR55 for every tonne of cane sold to the mills. This is unlikely to be enough to help mills with their cane payments.

Other proposals that are currently discussed include a minimum selling price for sugar and the creation of a 3 mln tonne sugar buffer stock.

Although India is not planning any direct incentives for sugar exports, rival exporters such as Brazil, Australia and Thailand could still lodge complaints with the World Trade Organization (WTO), saying such support will help the Indian industry sell overseas.

Government officials insist India's plans to directly pay cane growers would not contravene WTO rules.

The fact that ISMA is no longer making any other proposals can be seen as an indication that the situation is desperate.

Indeed, the numbers are frightening. By March 31 close to INR200 bln cane arrears have piled up and they could reach INR250 bln before the season is out. The largest part of this is owed by mills in Uttar Pradesh where the cane prices are higher than in the rest of the country. The sector there owes over INR90 bln.

Bajaj Hindusthan Sugar, which has 15 sugar mills, has sugarcane arrears of INR27.09 bln, while Modi Sugar, with two sugar units, owes INR5.14 bln, Mawana Sugars INR4.36 bln, Simbhaoli Sugars INR3.83 bln and Rana Sugars INR3.64 bln.

Companies' losses to deepen in 2018/19

The 2016/17 deficit on the Indian sugar market proved to be a short-lived blessing for the country's crisis ridden industry. Even though some mills still posted positive results in the 2017/18 fiscal year, most have already slipped back into the red again. This trend can be expected to accelerate next year.

Bajaj Hindusthan, by far the biggest producer, posted a loss in its sugar division after two profitable years. In the twelve months to March 31, 2018 Bajaj lost INR1.4 bln in the division against profits of INR3.6 bln in the same period in 2016/17.

Bajaj Hindusthan has 14 sugar mills with cane crushing capacity of 136,000 tonnes per day and alcohol distillation capacity of 800,000 litres per day.

The country's No.2, Balrampur Chini Mills, posted a profit of INR1.4 bln in the sugar business in 2017/18 against INR5.6 bln in the same period a year ago.

The company operates ten mills with a combined daily crushing capacity of 76,500 tonnes and alcohol production capacity of 360,000 liter per day.

The No.3 in the country, Triveni Engineering, posted a sugar profit of INR1.2 bln in the twelve months to March 31, 2018. This compares with earnings of INR3.6 bln in the same period a year ago.

The company operates seven mills with a combined daily crushing capacity of 61,000 tonnes and alcohol production capacity of 310,000 liter per day.

Shree Renuka Sugars reported a stand-alone sugar loss of INR3.1 bln in the four quarters ended March 31, 2018 as compared to profits of INR0.9 bln in the same period a year earlier. This is a new record high for the company.

Besides its two coastal refineries the company controls eight cane sugar mills with a daily crushing capacity of 45,000 tonnes. Its alcohol manufacturing capacity is 930,000 litres per day, according to the company.

The third company in this overview where the downturn in the sugar market has already caused the sweetener division to slide into negative territory is E.I.D. Parry. This company posted a loss of INR0.3 blnin the 2017/18 season against a profit of INR1.5 bln in the same period a year earlier.

The company operates eight sugarcane mills with daily crushing capacity of around 33,000 tonnes.

All companies suffered from a particularly poor fourth quarter when high costs and low sugar prices created particularly challenging conditions.

This will continue in 2018/19 and therefore the calls on the government to take immediate actions have become more urgent.

Remedy 1 - Boosting sugar exports

The central government has taken a raft of measures, including doubling the customs duty to 100% to prevent cheaper imports and scrapping an export duty and making it mandatory for mills to export 2 mln tonnes, the so-called Minimum Indicative Export Quota (MIEQ).

Meanwhile, the state government of Maharashtra is planning to provide sugar mills an export subsidy of INR5,000 (USD83) per tonne of sugar, according to local press reports.

Minister for Cooperation Subhash Deshmukh confirmed this and said the subsidy is being considered to help mills meet their quota under the MIEQ. Sugar mills in the state have been given a target of exporting 620,000 tonnes before September 30 under the program.

The export quota announcement in March had failed to excite millers due to low international prices. The industry emphasises that white sugar is presently trading at INR20-23 per kg and raw sugar at INR16-17 a kg, much below the cost of production of INR36.

This compares with local prices of INR26-27.

While sugar mills are waiting for a government subsidy, this strategy could backfire as international prices will fall further once India starts exporting. Traders said bulk buyers of sugar are demanding sugar at INR25 per kg from mills in Maharashtra. They argue that if exports do not take place then domestic market prices may fall as low as INR20 per kg.

Remedy 2 - Reviving the non-centrifugal sugar industry

To give cane farmers a viable alternative to sugar mills as their buyers, the Uttar Pradesh government has decided to revive and boost the state's jaggery (gur) and khandsari (unrefined sugar, made from thickened cane syrup) industries.

One plus for farmers in selling to gur or khandsari units is that they offer spot payment to farmers, without much supply and weighing hassles. Unlike sugar mills, which are also allowed a window of 14 days to settle payments.

At one point, there were about 5,000 khandsari units in the state, but now this number is down to 157. To incentivise these, the state government reduced the minimum distance from the nearest sugar mill for licencing to 8 km, from 15 km and waived all levies on the production of gur.

During its heydays the gur and khandsari sectors in all of India crushed between 50 and 60 mln tonnes of cane. In 2016/17 this had fallen to 25 mln tonnes.

Remedy 3 - Fuel ethanol

The Union government should use the fuel ethanol-blending program to reduce the growing sugar surplus, according to the industry.

So far New Delhi has only been mulling to reduce the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime for ethanol production to 5% from 18% now.

However, the sector is now demanding that it should be allowed to cut back on sugar production by stepping up alcohol output.

Traditionally, the industry makes alcohol from C-molasses, a by-product of sugar production. Going forward ethanol should rather be produced from B-heavy molasses, which contains considerably more sugar. However, if the mills cut back on the sugar output, they will have to be compensated with a competitive price for ethanol. A litre of ethanol from B-heavy molasses will have to be priced at INR52, about INR11 more than the INR40.85 at which the government had fixed the fuel ethanol value for the 2017/18 blending season (Dec/Nov) back in November 2017.

Given the distillery capacity in the country, the industry estimates it could divert about 500,000 tonnes of sugar to ethanol production by this measure.

At the moment New Delhi does not seem to be prepared to go that far. In mid-May the Cabinet approved an amendment of the National Policy on Biofuels which allows the blending of fuel ethanol made from damaged food grains, rotten potatoes, corn, cassava, sweet sorghum and sugar beet with gasoline.

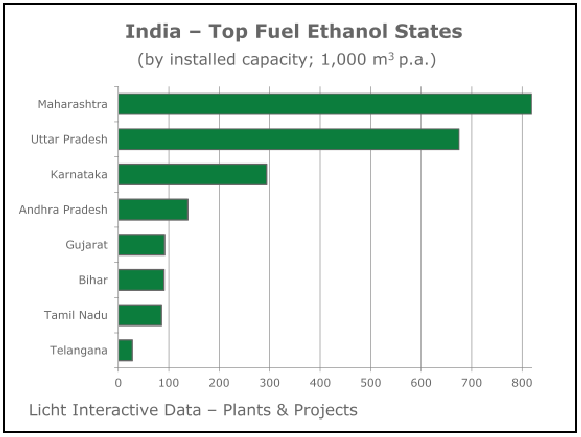

Currently distilleries are capable of producing 2.3 bln litres of fuel alcohol with actual production far below this level. In 2017/18, 1.0-1.3 bln litres could be produced. On top of that the ethanol industry also produces up to 1.1 bln litres of beverage ethanol. The production of industrial alcohol has mostly been switched to fuel alcohol production in recent years with the remaining facilities being capable of churning out 200-300 mln litres and the remaining demand being covered by imports.

The industry is also asking the government to simplify the movement of ethanol between the individual states. For example, moving ethanol from Uttar Pradesh to Haryana costs an additional INR4.15 a litre due to levies by the two state governments. Oil marketing companies do not reimburse this money because state governments are not supposed to levy such taxes under the GST regime.

Only Maharashtra and Karnataka have agreed not to levy state tax or control movement, according to industry sources.

Longer-term, ramping up the blending program to 10% vol., as has been official policy since 2009, could help as well. However, this will require massive investments which will have to be facilitated by competitive interest rates through the sugar development fund.

So far, a clear policy announcement is lacking on this front, the industry criticises.

For the sugar industry the fuel ethanol program is a key factor in its survival strategy. In the lean sugar years 2013/14-2015/16, income from the distillery business was crucial to keep up operations. In 2016/17 the importance of the scheme has diminished as sugar prices recovered. However, as the government steadfastly refuses to link the sugarcane price to the sugar price, mills' profits will remain highly volatile. Therefore a secure ethanol market will continue to provide a much needed safety net even though it is now less tightly knit after the recent price reductions.

Record run to continue in 2018/19

While 2017/18 season may be bad, 2018/19 may be even worse as sugar production is forecast to rise further.

All measures that have been taken so far will be too weak to deal with maelstrom of overproduction and the industry's apex body ISMA sees massive subsidies as the only way to avoid disaster.

As so often the government finds itself in a most delicate position. If it shells out generous subsidies to the sector and Indian sugar finds its way to the world market (as it surely will) its actions will most likely be scrutinized by the WTO. If it announced direct export subsidies, the WTO will also step in but on top the world sugar price will slide further which could easily neutralise the support payments. If it does nothing, many mills will go bankrupt, which in most instances will bring hardship to their surrounding rural communities.

As its electorate will most likely be more important to the Modi government than international trade rules, it is likely that more measures to get the surplus sugar out of the country are in the pipeline. The victims of this development will be other sugar exporters as well as India's state coffers.

As the crisis mounts the government will also need to take a fresh look at the feedstock mix for ethanol. The insistence on C-molasses as exclusive fermentation substrate seems overly cautious given the surplus scenario.